Türkçe | Français | English | Ελληνική Alerta.gr

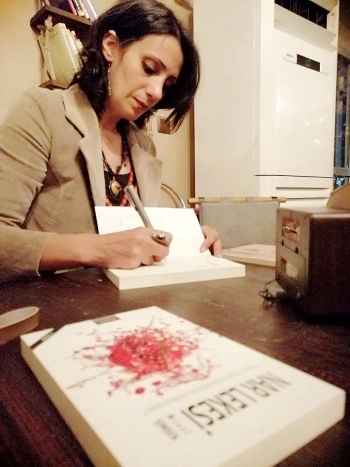

Meral Şimşek is a Kurdish author, currently threatened. She was born in 1980 in Diyarbakır. She became known through her poems, novels and short stories. She works as editor for magazines and publishing houses, writes lyrics and composes songs. She is a member of the Kurdish PEN, of the Kurdish Literary Association (Kürt Edebiyatçılar Derneği) and of the Association of Kurdish writers of Mesopotamia (Mezopotamya Yazarlar Derneği).

She has published three collections of poetry (Mülteci Düşler, Ateşe Bulut Yağdıran, İncir Karası) and one novel (Nar Lekesi). Her writing has been translated into several languages and often awarded prizes: in 2016 in Irak, she received the second prize and in 2017 the first Deniz Fırat poetry prize. In 2017, the third Yaşar Kemal poetry prize, in 2018, Diyarbakır’s best writer/poet in the Altın Toprak prizes, the first prize for her short stories in 2020 by the Federation of Alevy Unions of Germany (AABF). The Comma Press selection in England, 2020. And in 2021, the Hacı Bektaş literary prize awarded by UNESCO-AABF-KSK. In Germany again, the first prize in short stories for Dersim Gemeinde e V. Köln (The Dersim massacre).

Meral Şimşek was prosecuted and condemned for her writing which focuses on social realities. Some of her trials are still ongoing.

We spoke with Meral Şimşek whose remarkable pen Kedistan has attempted to present in different languages to its readers for a certain time already. You will find these works in this archive.

Dear Meral, you are before Turkish tribunals for your writing, your books and your words. At the same time, you have been awarded several prizes… I know the problems you encounter, like other Kurdish and progressive authors are nothing new.

We constantly come across an expression, particularly in mainstream European media, an expression we simply cannot stand: the sentence “everything began with the failed coup d’état of July 15 2016”, which shows up in interviews, news items and even in documentaries. Whether you interpret this with indulgence as “a lack of understanding” or “ignorance”, or deliberately, this suggests the notion that Turkey was a very democratic country but that Erdoğan messed everything up… We think it’s crucial to repeat each and every time, unceasingly, that Erdoğan and the AKP regime are a power structure that has appropriated the existing nationalistic and fascistic policies existing every since the founding of the said Republic of Turkey and that keeps on implementing the “tradition” of Turcity. These are the reasons why I felt the need to add these words.

With your identities as a Kurdish woman and author, the reality of this “permanency” is also present in your life. When and how did the oppressions, threats and arrests against you begin?

In fact, the greatest of the false notions, one that is shared socially, is to think that tyranny appeared with the current ones in power. Because powers are only the guards and prolongations of the existing system. Those who consider what is currently going on in Turkey as something new, make the problems more and more unsolvable. The tyranny is nothing new, it’s simply that it applies to a wider spectrum. If we consider to what the Kurds have been subjected, if only over the past 40 years, it will be obvious the extent to which the atrocity is deeply grounded and systematic. There’s no need to go back much further in the past to refresh memories.

Indeed what I’ve experienced is unfortunately not limited to recent times. This process affects my family in the wide sense of the word, and also my immediate one. I was subjected to a first detention and torture when I was barely 13 years old. During official and non-official detentions, on a number of occasions, I was subjected to all kinds of torture, including rapes. My brother and my sister were murdered at three year intervals during this same period. My brother does not even have a burial site, still. Many members of my wider family were tortured, imprisoned for several years and others were assassinated.

But the serious and concrete attacks against my literary existence began in 2019. I was illegally seized by security forces in Malatya. I was threatened with death, subjected to blackmail. I was ordered to do as they said, to shut up, under the threat that they “would end my literary life.” Faced with this, of course, I did not remain silent. I took judiciary measures through lawyers and I also made the threats public through press releases. Unfortunately, while no real and concrete investigations were opened against these individuals, quite the opposite occurred after a certain length of time when trials were opened against me, accusing me of belonging to an illegal organisation and of spreading its propaganda. Finally, I can say that a kind of revenge operation was carried out against me because I did not keep quiet.

At the tribunal…

In Turkey, prisons are crammed with journalists, politicians, artists, writers. The regime incarcerates a number of opponents who have done nothing other than cry out for “Peace”, labelling them as “terrorist” and, in order to do so, using as an excuse a signature, a book and even sometimes a sentence taken out of context or a drawing, a sharing on social networks. What were the “excuses” used to judge you? Were you condemned? As there other trials ongoing?

As I said, alas , the persecution is directed in multiple directions. There’s an attempt to control and extinguish any and every voice considered as oppositional. My judgment process as pertains to literature began with a raid on my home on December 9 2020, using these same excuses. Then, my literary creations, some of the awards I received and literary initiatives in which I participated were used as motives and trials were opened against me for the crime of belonging to an armed organisation, and propaganda.

During the trial, I was faced with prohibitions against leaving the territory and the obligation of signing in at the commissariat. In fact, these judiciary controls amount to a kind of incarceration because your living space is thus limited. During this period, I was unable to stand the situation and I attempted to leave the country. But in the country where I was able to land, in Greece, I was subjected to torture by the the police and, as if that had not been enough, I was thrown into the Maritza river and left to die. Despite everything, I managed to survive and to return to Turkey where, unfortunately, I was sent to prison. As if they were not sufficient, to the prosecutions against me were added a new trial for having “breached the borders of a military zone”.

Last October, the local tribunal ruled in the matter where I was prosecuted for belonging and propaganda. While I was acquitted of belonging, I was sentenced to 15 months for propaganda. But these decisions are not final, we are awaiting the decision from the regional court of appeals. We don’t know if the result will be in my favour or against me.

Of course, the first two hearing on the matter involving my passage in Greece have already taken place. A sentence of up to 5 years has been requested in this trial and the next hearing is on January 11. I have no idea of what the verdict will be.

The fate of refugees forced to leave their homes for reasons such as war, pillaging, oppression, violence, is strewn with inhuman difficulties that can also lead them to death. You met with unimaginable violence in June 2021 when you attempted to reach Greece. Strip searches, confiscation of your money and phone and what is more, the violation of your right of asylum, as well as the fact that you were beaten and thrown into the Maritza river…

I know that returning on what you experienced rekindles your traumas. And I’m asking questions here that will re-awaken those terrible moments for you. I am sorry for that. I dare do it because you have begun writing about your experiences with your magnificent pen of which we publish translations in Kedistan… What does returning to those moments mean for you?

First of all, I wish to say that we are not the ones who should be apologising to each other. Yes, what we are experiencing is rather difficult and painful, but shedding light on the truth will not be possible if we do not express all that.

The event in Greece is obviously a huge disappointment for me. Because as one who has lived through and continues to experience all kinds of State violences in Turkey for a number of years, I considered Europe a place for living where I hoped for the proper functioning and respect of the law. Yet, my experience demonstrated that, for those of us who resist, violence and fascism know no borders.

Of course, I find it painful going back to those moments. Just as when I remember the atrocities I lived through earlier. Yes, I have survived miraculously, as I did in the past. The possibility that I would lose my life was so high that I still can’t manage to believe I pulled through. That is why I am still receiving psychological aid at the moment. Because on that occasion, all my past traumas also resurfaced. I had to receive serious surgery these last few months. In fact, it was the ninth surgery I’ve experienced because my body is badly damaged. So, this latest period has again wounded both my soul and my body.

Your writing usually focuses on Kurdistan, the lands where you were born and where you grew up, and the Kurdish people to which you belong. While we were talking, you told me “I work on the reality of Kurdistan and of the Kurdish people.” That reality includes many years of oppression, persecution, massacres, denial of the language, of the culture, of the identity, in short, the denial of the existence of a people. Unresolved assassinations, torture, misery, the treatment of women but there is also of course a strong spirit of resistance and an unrelenting struggle. Is your family not a piece in that ensemble?

Yes, alas, my family has suffered a lot, as have thousands of Kurdish families. My brother and my sister were only 19 when they were assassinated. It was traumatic for us, the remaining brothers and sisters, our mother, and will remain so for all our lives. My father is no longer alive. He died in pain also.

After all these losses, to be able to go on resisting is in fact another challenge for the Kurds. Imagine dying, being tortured, denied, but despite all that, you go on resisting because, the moment you would stop resisting, your true disappearance would be unavoidable.

Where does your motivation to write and to express yourself in various ways come from? What feeds the strength you find in order to continue?

Of course, writing is not only a matter of talent, it must be fed. As a general rule, your own life is the way to feed it, what you have witnessed and, of course, your world view. The topics I cover are painful stories, this is true, but I attempt to treat them not only from the angle of pain. Quite the opposite, I attempt to instil the conviction that hope exists and that the land will become beautiful. Because if there are still people who resist despite all the suffering and the cruelty, hope still exists very strongly. I simply attempt to be a part of this hope. And I must say that I owe it to my belief that keeps on growing within me and never dies.

Your books have not yet been translated in French I sincerely hope this interview will attract the attention of a publishing house… I discovered a new book of short stories will be out soon: “Arzela”. While this book is judged and condemned in Turkey, one of the short stories in the book, the one with that title, was selected for an anthology Kurdistan +100 prepared by Comma Press in the United Kingdom. Arzela is the name of a flower and of a special concept. Can you tell us something about it?

Of course, it would be a great joy for me if my books were published in French. Obviously, all authors would like their writings to reach a readership in different languages. But French is one of the most magical languages for me, and for me, that would be very precious. With the translations you have done, I understood that even better.

Arzela: a wild rose endemic strictly in the soils of Halfeti in the province of Urfa. The region’s microclimate and the composition of the soil allows the roses to remain black, even after blooming. Plantations in other regions produce red roses.

So, Arzela is a collection of seven short stories and an introductory article. My story Arzela is one of the short stories in the collection and the one given that name was considered worthy of entering the Kurdistan + 100 anthology, which is a very important selection in the United Kingdom. However, this story Arzela, despite the fact it has yet to find a readership in Turkey has become one of the reasons for my trial and condemnation. Not only Arzela, in fact, but also many of my awards and works are used against me in judicial proceedings.

As for Arzela, yes indeed, it is the name of a special variety, a “black rose”, “karagül”. And the only place in the world where it grows naturally is on Kurdish soil. From my point of view, this was very important for the integrity of the meaning in this context, and I think it will also be the case from the reader’s point of view.

What are your plans for the coming days?

This collection of short stories, Arzela, will be published soon, it will be my fifth book. After that, new editions of my four first books will come out since the first editions are out of print and re-editions have not been possible since 2019 because of my judicial proceedings and what I went through. Apart from these, I have several other books ready for publication, and I plan to bring them to public attention a bit later.

Currently, I continue writing, but I also work as an editor. Also, since partial translations of my productions are occurring in various countries, I’m also working at keeping all of this as an entity.

In fact, I must say that no matter what I go through, I attempt to keep on navigating at the heart of literature and the arts, without ever giving up or becoming tired.

I thank you with all my heart for this interviews, and also on behalf of our readers.