Türkçe Nupel | Français | English | Castellano

Translation of a text that resonates with what is happening on the Belorusian borders. Here, the no man’s land is a river but the mentality of the smugglers, and that of the soldiers, is the same, with money and inhumanity serving as the heart of the exploitation of human misery…

Despite my efforts, I didn’t manage to wipe the worry off my face when my eyes met those of Dicle who was trying to hold onto our bags close to her at the other end of the boat — a boat even dirtier than the waters of this river that runs between borders.

At moments like these, I didn’t even have time to think that this effort was stupid. I took my eyes off Dicle and continued struggling with the two others who were in the boat with us. At that moment, I saw that one of the masked men on the shore was yelling and gesticulating to those in the boat “throw them out!”. There was no need to know the masked man’s tongue. I understood I was about to be thrown into the river. Shortly before this, the owner of this same voice, unable to stand the fact I was resisting him while he thrashed my thighs and back with the butt of his gun, had said in a language I speak “shut up, you’re gonna die!”

In a fraction of a second, in a burst of energy, I grabbed the hand of the man in the boat, the oar turned rotten from spending so much time in the water, and I struck him in the face. Because of thirst, hunger, fatigue, worry, and the punches landing on my body shortly before this, I couldn’t manage to control the oar well enough. With the shifting of the boat, the second man panicked. He attempted to grab the oar out of my hands and throw me into the river this time.

While the boat pitched and rolled, Dicle came close to falling overboard, attempted to help me, but couldn’t. The man whose face I had struck, recovered. My whole struggle was annihilated. He regained his balance and managed to send me into the water. But the oar was still in my hand.

I took advantage of the floating oar and managed to drift toward the other shore, but just for a moment. The boat moved closer, two hands pushed my head down into the river. The oar was theirs again.

I did not know if the water was entering my lungs, my nose or my mouth but the muddy river was swallowing me. How do you do the breast-stroke again? Everything I knew was erased. The voice saying “Shut up, you’re gonna die!” still sounded in my ears. As I went up and down in the water, the image of two children appeared.

“Mummy, don’t give up!” they yelled.

What are they doing here? The river is swallowing me, I’m struggling. The children yell again,

“Mummy, no, don’t leave ! Get on your back, on your back!”

What are they doing? How old are they? I throw myself on my back, in the water’s arms. Where are my mother’s arms? How angry my mother will be with me when the river swallows me. I will be the third of her lost children. What is more, without a tomb, like my brother ! How many times have I lived this sensation? This must be the final one.

My hair carries the whispers of the river to my ears, while the wings of the sun look me in the eye, crying. Where is this river carrying me? Does the Maritsa 1end up in the sea or will I be dragged through the mud? At the moment when I close my eyes, listening to the river’s whispers, the children yell again.

“Mummy, go ahead, beat the water with your feet!”

My legs, crushed by the hits from the muzzle and the truncheon have absorbed the mud from the river, like sponges. How could I manage to beat my feet? And the river is busy swallowing me. Am I in the process of leaving or of staying, I don’t know. Are my feet moving? I don’t know that either. My hair carries the voice of the water to my ears.

“There, give yourself up to me!”

I’m about to let myself go in the river’s voice, a woman’s voice finds me.

“Quick, give me your hand!”

The river grabs me by the hair„ the woman by the hands. The hands of the river and those of the woman are so different. When my body thumps against the stones on the shore, I realise I am alive.

But how? I still can’t breathe. Every cell in my lungs has filled with the river’s dirty water. I close my two hands into a fist, I press on my stomach, on my diaphragm, several times. The dirty water pours from my mouth, from my nose, with coughing fits that make me nauseous, but the freer my breathing becomes, the more I come back to life.

Did all this last a few minutes, or centuries? If truth be told, it doesn’t matter, I am alive. Giving myself up to the earth’s skin, I meet the eyes of a woman. Dicle. She is alive! While the sun caresses my sodden body, I smile at her. The smile illuminates my face. My smile is painful, but happy to be alive. I smile, we are alive.

From close up, sounds of shots on the other shore, the sounds of cars speeding away. The barking of dogs moves closer. If Lili were here, she would be miaowing out of fear, hiding between my legs.

Dicle holds my hand, and in the other hand, she carries clothing that is slightly humid, but not muddy. Those hands, those of Dicle, are so different from those of the river that were pulling me into the depths…

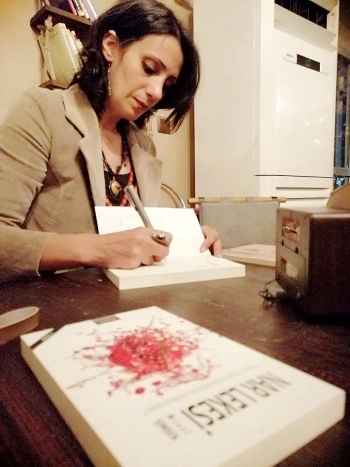

Read also on Bianet : Kurdish writer Meral Şimşek tortured with strip search by police in Greece