Français | English

And that is how one becomes a “terrorist to be locked up”. A judge, self-proclaiming himself as an art critic, thus decided in 2016 what almost three years of Zehra Doğan’s life would consist of: an incarceration… because of a drawing.

Next!

This “injustice” masquerading as censorship was in fact the political result of what appeared as a “denunciation” of crimes committed by the Turkish army, through the diverting of a photo. The virtual drawing was done on a graphics tablet and, thus, will never exist except as a digital file.

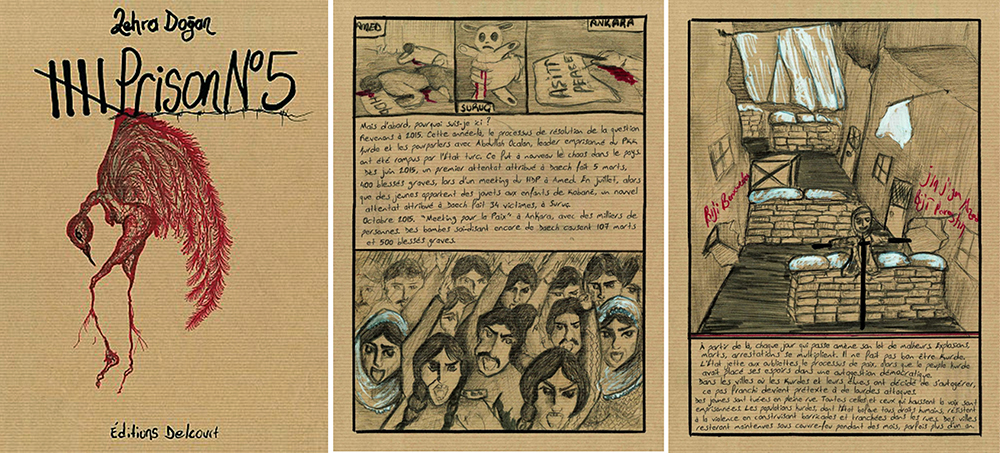

As we know, the sentencing opened up for the journalist and artist Zehra Doğan a period in her life she will find as hard to leave behind as one does the period of one’s twenties. And those years, most definitely, real, we can find them in her testimonials but also as hundreds of “prison works” as well as in her now-published prison letters. Added to these now, a graphic novel, also done in clandestinity, escaped sheet after sheet, next to works done on fabrics and other materials passed on furtively.

Day after day, Zehra will insist on pursuing what is both a diary and a homage to those before her who spent dark hours, and worse, in the Amed gaol, prison N° 5. Those who will read both the prison writings published under the title of “Nous aurons aussi de beaux jours” and this graphic novel to be published by Delcourt in March, will understand what the words “resistance” and “common” mean. For, in this gaol, what were crossed were not “the limits of art” but those of humanity. And faced with this, an artist knows that she can only transmit a “reflection” of this violence, but one that cannot leave us indifferent.

But is it truly the role of an artist, even if she is directly concerned, to “trouble” us this way in our daily life? Doesn’t she have other things to do instead of showing us a disturbing violence? Was the judge, that improvised critic, right back in 2016? Isn’t going beyond the “limits” contrary to every propriety.

I’m not raising these questions in the void. Because Zehra, free today, sees herself rebuked in opinions that almost bring us back to the judgment in 2016, this time for public performances expressing recent or past violence tearing the Middle East apart.

She had just been liberated and taken refuge in London in 2018 when the prestigious “Tate Modern” proposed that she do an installation. Jumping on the opportunity she exhibited what was also a long thought-out artistic project which consisted of objects in daily use she had collected in destroyed neighborhoods in Kurdistan where she had been as a Kurdish journalist, in order to provide traces of the violence and the oppression exercised against the populations. She titled this “Ê Li Dû Man” (What Remains). Only objects and texts evoking the suffering, like the piles of shoes in a concentration camp that would catch us in the throat as these objects were meant to make us understand, such was Zehra’s intent. She accompanied this with sounds and a video testifying of life on a barricaded street, under fire from the Turkish army, and a brochure.

While it would have been easy to take exception with the form of this installation assembled quickly, the criticism of “transgressing the limits” soon showed up. She was then accused of a “pornographic” stage setting of violence. Nothing less! Some took to the social networks with this argumentation, also implying of course that this was in the service of a sought-for ” notoriety”. The polemics soon died down, following the publication of supportive “criticism” from persons well known in the Kurdish movement. Well, let’s not exaggerate, social media are not judges.

This accusation of “pornography” resonates in an odd way with the one aimed at her in prison, when she used her menstrual blood and that of her co-detainees. Here also, the “disgusting” went beyond the limits of art and of a certain red line. But while Zehra had responded strongly, as a woman, to her accusing jailers, in London, liberated from prison and still under the influence of the three previous years, this accusation reached her like a poisonous thorn.

As an artist, even a Kurdish one, was it legitimate to denounce these atrocities? Was there need to liberate these daily objects of the demons and the violence haunting them? Could art and politics co-exist? And how?

This important at the Tate Modern was important in more ways than one. First of all, of course, the fact of reaching a “celebrated” space for Contemporary Art, following the support she had received from Banksy and Ai Weiwei, opened up for Zehra Doğan, as an artist, doors usually reserved for “established values”. Such is the world of Contemporary Art and opening a breach in it, as woman moreoever, was essential for the rest of her artistic nomadism throughout Europe. The numerous other exhibitions cannot be ignored either, because they brought solidarity and her art, thus acknowledged in more conventional artistic venues, allowed Zehra’s work to be seen while leaving her a total freedom of expression.

This freedom of expression, or rather, this freedom of creation continues to be the one she speaks, exhibits, publishes, stages, in the same collective spirit as the one she had in prison.

2019 Angers, France. Photo ©Jef Rabillon

“I am an artist who is political”, she says. Because, of course, the question is always at the forefront. And she adds “I am such because a woman, and born Kurdish”.

And she proved it during the 2020 exhibition in Istanbul. A hoped for exhibition she only thought possible in her dreams. Brave organizers confronted the potential ire of the regime. And despite the pandemic, and the impossibility of a large opening, it was a success. Here at last, those who only saw in her, at best a “propagandist” or at worse “an artist using the Kurdish vein” had the opportunity to discover through her exhibited works the full expression of the artist, the woman, the Kurd free to speak, forged into politics by the repression of her people. The social networks did not emit a peep against her and even the regime was silent.

Her journey in these almost three years, from the Tate to Istanbul finds her being classified among the “100 contemporary artists that matter” by Contemporary Arts milieux, without her having ever renounced anything, “coded” anything, and after going beyond so many times “the limits of art”. “What’s the point of putting us in prison. We come out stronger.”

But thinking that Zehra Doğan does not constantly question her artistic practice and the way political content keeps spilling out of it would be to miss the point and not even see it.

For Guernica, Piccasso did not paint planes and bombs. And yet, a judge, a critic or a prosecutor could have told him he had “gone beyond the limits of art”.

“Hey Picasso, tell me, what are those scattered limbs doing, those women imploring the sky, that frenzied cattle, in an evocation of the Spanish revolution? Why didn’t you outline the “international brigades”? Why, instead, this suffering in the horse’s flaring nostrils?”

That is one way to envisage art and politics: reality, nothing but reality in the service of the cause. It reached its peak recently in China after long being a feature under Stalin. But this art is also coded in its way, since it “represents” the martyr rather than the body, heroism rather than the victim. And that is probably the turning point at which a few “critics” in Istanbul were waiting for her.

Zehra has freed herself from these “militant” codes and of those of the “committed but not reckless” artists either, those who symbolize oppression with a half-erected brick wall in the middle of an empty hall during one Biennial or another.

In this respect, I would like to return to an artistic performance Zehra Doğan has just done in Sulaymaniyah and show how, really, I would probably have been a good “judge”.

On a large piece of white fabric, Zehra has a film in black and white projected. It is not fiction, but a documentary where she is seen among small anonymous and scattered tombstones on a barren ground. Under a heavy and threatening sky, she walks through this space and lays braids of women’s hair in homage on the white stones. This filmed documentary tells the story of assassinated women whose anonymous remains were buried there, as if thrown into oblivion on an uncertain date.

In fact, this documentary is also staged although it is the reflection of a reality anyone could also discover, two steps away. This reality is projected in black and white. Is it truly a reality? For having adapted into French the publication of Zehra’s prison letters, I know only too well this theme of the reflection which she uses so well. She has integrated it into her practice as a plastician, to express the gap between art and reality, a sort of allegory of Plato’s cave, all her own. And what could be more creative for an artist than to reconstruct this reality from its reflection

And in this artistic performance, she gives rise to the pain, through color, of the life projection from the blood of the living and of the dead. She paints her body, paints on the screen, recalls the violence experienced by these women whose very name has been forgotten. But she does not praise this suffering, does not take pleasure in it.

No part of this artistic performance can be separated from it, not even those moments where Zehra covers herself with the color of the exploded pomegranates, while the film screen comes to life. The extremely terse text linking the film and the creation is also indispensable.

She talks about it here also.

This “grief of the land”, these feminicides are violently reconstructed in the light, in public.

Neither heavily symbolic, neither denunciation in which political words would exhaust themselves. That is all of Zehra’s art, and of her woman’s cry against forgetting that invites to search for the reason why, now, and in the history of the scene.

Publication: March 2021 Editions Delcourt

Zehra Doğan will soon be exhibiting in Berlin at the Maxime Gorki theater: a number of works, from the period of her imprisonment and, again, the original artwork of her graphic novel. This ongoing pandemic will have slowed down her nomadism but not her creativity. Where prison did not succeed, a confinement seems laughable.

She will return from Kurdistan with the ferocious will to always go beyond the limits of art, and to let it be known, since she has not found such limits yet.