Français Ballast | English

The English version of the article published in Ballast, on October 7, 2021.

Images of Rojava fighters have circled the world over– notably following the battle of Kobanê in 2015 where these fighters contributed to the ousting of ISIS. But this media spotlight often came with an eclipsing of their ideological motivations. In October 2014, a member of our editorial staff met with Sêal, a young fighter from the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ). Seven years later, he attempts to find her again and quickly learns that she was among the first fighters killed during the offensive against ISIS in the regions of Tabqa and Raqqa in 2017 – two important fiefdoms of the Jihadist movement. In order to tell her story, he then takes off to meet her family and people who knew her.

By Loez

May 2021, on the road to Qamishlo. Sitting in front of a shawarma in a small restaurant where we are taking a break after driving since the border crossing at Semalka – where the Tigris divides the north-western part of Syria from Irak – I show Alan a photo of a group of YPJ fighters. The photo was taken at a base in the area around Tal Elo, not far from the town where we now find ourselves. The one fighter I’m most interested in stands in the back row, completely on the left. This is not her unit. Sêal had followed us after we had met her family and as we headed to observing a training session of young fighters, with whom she stood for the photo. Alan recognizes several of the young women. Two of them are his cousins: one of them is married, the other is still fighting. Another of the young women has become a kadro: she has joined the PKK guerilla and the armed combat against the Turkish army in the mountains of Northern Irak.

In 2011, Alan came back from Damascus where he was studying geology, in order to enlist in the revolution starting up in Northern Syria. He quickly joined the YPG, as did several of his brothers, before spending a long time working with Yazidi refugees, then, with the media. His smiling face and good humor are familiar to many among the Autonomous Administration 1 as well as in the armed forces. His family is heavily involved in the political life of Tirbespiye: his father was mayor for several years and his brother, Rêwan fell a martyr in December 2013. Having carefully examined the photograph, he hands it over to one of his acquaintances, the commander of the YPJ, so that she may make inquiries.

The answer lands on the following day: Sêal is no longer. She fell a martyr in 2017 in the province of Raqqa.

YPJ Center in Girkê Legê, October 2014: Sêal is on the right.

Girkê Legê, end of Octobre 2014

This is my third trip of the year to Rojava. I’ve had several meetings with YPJ fighters, organized in non-mixed units since 2013. Self-defence is one of the basic tennets of democratic confederalism, the political system based on direct democracy and women’s emancipation, a system militants have attempted to set up since 2012 in Northern Syria in the zones liberated from the Syrian regime. For the women, it is also a way to claim their proper space in society by participating in their own protection. That time, I had asked if I could possibly meet one of them in her family setting. After a few days, I received a positive response from the YPJ higher command.

We went to the base in Girkê Legê. This was my first meeting with Sêal. The young woman was smiling, shy; she conveyed an impression of serenity. Sitting with two comrades, a man and a woman, she was braiding the fringe of a large green scarf they often wear in winter. Her commander came with us for the visit in her family. She had chosen to pull her away from the fighting, I am told several years later. We head out. The autumn sun was still warm: huge wheat fields stretched out far into the South, toward Jazaa 2. On the horizon, plumes of black smoke rose from makeshift refineries where unemployed peasants ruin their lungs and their skin. The front with ISIS had been pushed back just beyond these, some ten kilometers further away.

At the time, the family still lived in a small earthen house on the edge of the village of Gir Ziyaret. The parents were not there. They had to leave for a medical appointment for the father, Sîleman, whose health was fragile. Five years later, her mother, Halima, still regrets this. This is when I will learned that such visits to families were extremely rare. We were then greeted by her two brothers and their wives. We drank tea in the long main room. Sêal remained with a gentle smile on her face, but didn’t respond much to questions. What was she thinking of, at that time? Was she trying to understand what this foreign journalist expected her to answer to questions that weren’t really very clear? Her commander, Zilan, ended up monopolizing the interview: she was a woman in her forties, with deeply wrinkled features, with the hard but pleasant bearing of those who have experienced the PKK guerilla. She fought several years in the mountains before being sent to Northern Syria, from where she was a native.

Sêal on the left, with one of her sisters and her sister-in-law in October 2014

Sêal was happy to see her brothers; she picked up one of the babies. The family posed for group photos. Her cousin Mazlum joined us. Before her own death, he will fall a martyr in 2015, during the second operation to reclaim Tel Hamis from the hands of ISIS. In the end, there was no time or opportunity for a longer exhange. I didn’t learn much more about who was this young woman. A photo will remain – Sêal, sitting next to her sisters-in-law. The one in military uniform, her weapon close at hand, the other with a baby in her arms. Two different destinies. And unanswered questions: what led Sêal, like thousands of other young women, to join the YPGJ? In what way did this commitment change her life?

Gir Ziyaret, May 2021

The village of Gir Ziyaret nestles along the road leading from Tirbespiye to Gire spî, a bit before the entrance to the town. It is a big village at the foot of an artificial hill that serves as a cemetery, like so many you find in this region. The road that leads to it, dusty and rocky, is not asphalted. A young man on a motorcycle, to whom we put the question, leads us to the home of Sêal’s family we weren’t able to find despite indications we had been given.

The space has changed. A metal gate opens onto a large courtyard. On the left is the grey mass of a large, recently built house. On the right, the old beaten earth house has disappeared: in its place there is now a garden where clothes are drying on wooden slats. Hens and ducks keep to the shade of a large and well-trimmed tree. Outside, Sêal’s mother greets us, a cigarette between her lips. The scarf on her head and tied around her neck, lets a few wisps of white hair stick out. Sêal’s brother Reber is also on hand.

The walls of the greeting room are empty, save for one side on which hang several large photographs of Sêal, sometimes alone, sometimes among other martyrs. The ground is covered in rugs. We sit on mattresses, our backs against cushions. When Halima starts talking about her daughter, a few tears roll down her cheek which she wipes away with her hand.

In May 2021, the new home of Sêal’s family, built after her death

Sêal was born in 1994 or 1995, her mother doesn’t quite remember. She was named Newroz. A name that is not in the least bit insignificant: Newroz is the feast held every March 21st, celebrating spring – for Kurds it has become a symbol of resistance. This is because Sêal’s mother was already a sympathizer of the PKK’s leader, Abdullah Öcalan, whom she admires. She chose the names of two of her sons to honor him. In the family, she is a Kurdish patriot. And poor. Prior to the revolution, the father, his seven sons and five daughters worked as field hands for wealthier owners.

The one who was still known as Newroz left school in the 6th grade – thus, around 12 years old – to join her sisters in the cotton fields. As a child, her mother recalls she liked to sit on the rock facing the tendûr, the bread oven while she baked hand-flattened bread dough. She said the oven was her horse. When the revolution began, the eldest and the youngest sons quickly joined the YPG. The family did not flee, the mother emphasizes; Newroz was the next who wanted to enlist. This was in the last months of 2013, prior to the Tel Hamis operation. “Not in a sneaky way, thank God”, sighs Halima, who attempted to dissuade her, explaining how this was a heavy responsibility, a hard commitment, she would not be able to bear the constraints of military life. But Newroz did not give up. She wanted to go. She said goodbye to everyone and left in order to be reborn as Sêal Cûdi – litterally, Sêal means “the shadow of the the flag” or “the three flags” ; interpretations vary whether this means sê as in shadow or sî, the number three… In any event, it is a patriotic name. After her training, her knowledge of arabic and of kurdish send Sêal on the roads of the region with a cadre from TEV-DEM 3, Eli Shemo, for work that was more political than military. For close to a year, she translated at meetings with arabic tribes, helped to recruit new fighters…

On several occasions, her parents attempted to bring her back home. Her father at first, whose round, tanned face resembles than of Sêal. “She did political work. After that, I told her to stop: ‘Daughter, I don’t want you to die.’ But she refused my request. Sometimes, when she was in the village, she did not come home, she stayed with the heval [“comrades” in Kurdish] and in the martyrs’ homes. She carried the weight of the revolution on her shoulders. ”

Sîleman did not see the change in his daughter. Sometimes in disbelief he would tell his friends that she was not all that brave; then, he would be told: “No, you’re wrong, she is the bravest of the heval.” He remembers an anecdote. In 2012, the village was threatened by the arrival of forces from the Islamic Front, affiliates of Syrian rebels. The inhabitants took up their weapons to organize their defence. Sîleman picked up his rifle and started heading for the front lines when he turned around and saw his daughter following him, determined to protect him.

Later, Halima had two of her friends, Arab girls from the village, send her a message. By then, Sêal had been enlisted for three years: her mother considered it was time that she came home. When the two girls came back, they told Halima: “We couldn’t convince her to come back but she about about to convince us to join the YPJ.” After a silence, Halima adds: “The two girls are still alive today.”

Halima and Sûleiman, Sêal’s parents and her brother Lezgin, in May 2021

The last time her family saw her alive was in early 2017, some three months before her death. She had obtained three days of leave but her comrades did not come for her before the fifth day, which angered her. The two fighters who came for her were killed when she was. When they arrived, she yelled: “Heval, you forgot me, you said three days and now, it’s been five!” They answered: “How dare you say that? We never forgot you!“Apparently her old grandmother sensed this was the last time she would see her. She stood up to follow her, then the rest of the family followed. “That was the last time; after that, I saw her in her casket”, murmurs Halima.

Shortly before dying, Sêal appears in an interview to a Kurdish station. “We are heading to the operation in Raqqa, we will avenge our martyrs, success is with us.”

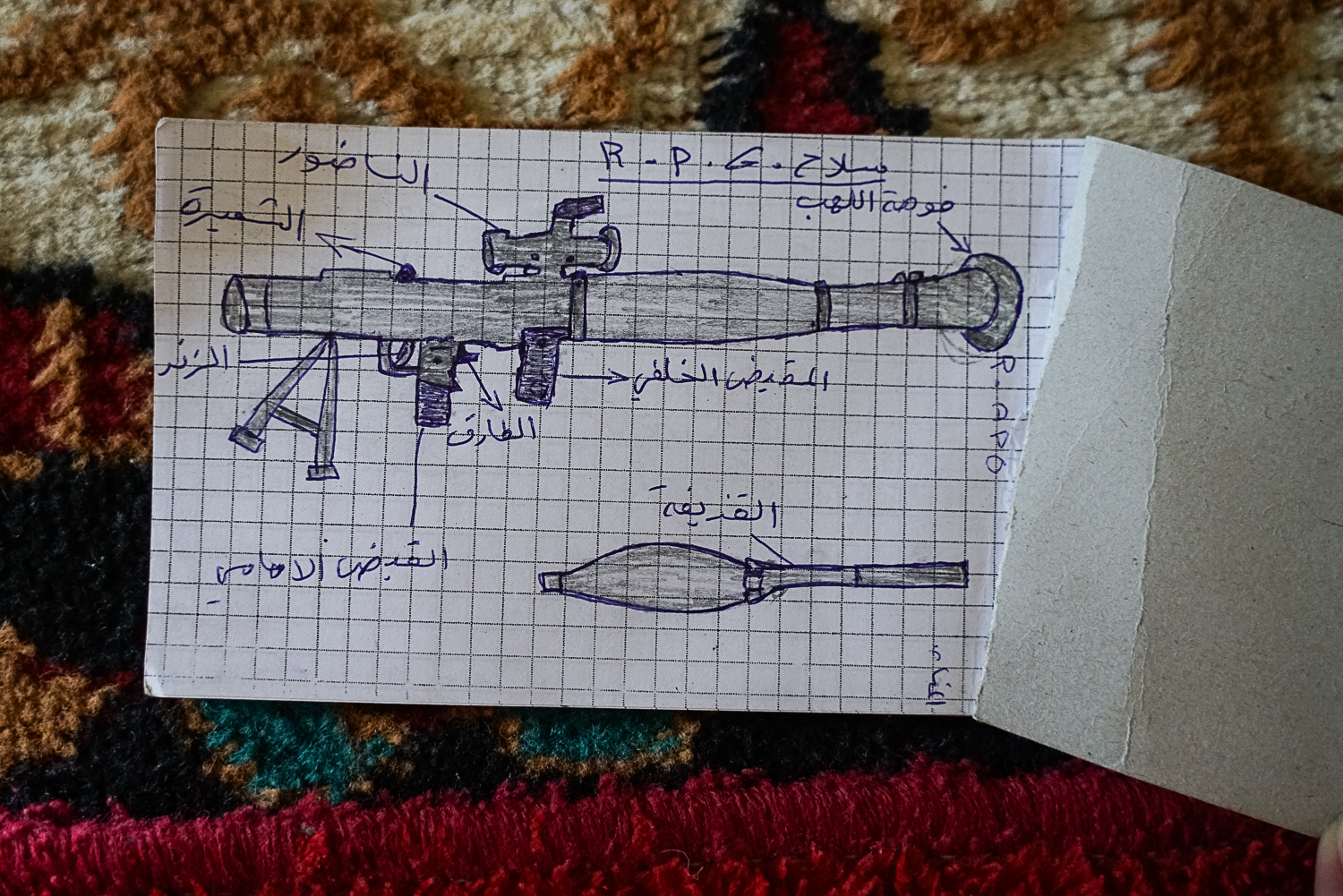

“I still have her books by Serok Apo [nickname given to Öcalan] and her small Coran. Her friend told us she read them when she was tired,” says Halima. She often wore a scarf tightly wound around her head, with a border of beads, all of the same color – not the flowered model often seen on Kurdish women fighters. From what we are told, she was always on the front lines with the elite groups, the kadros, trained in the PKK guerilla in the struggle against the Turkish army. Fighters trained to night operations. Sêal had specialized in heavy artillery: 12,7 millimeter DShK, RPG rocket launchers, PKC machine guns. Perhaps field work had given her the endurance and strength required to carry the ten kilo (barring ammunition) of the Russian machine gun. Thus, we see her on a video, lifting it on to her shoulder before leaving on operation as the night falls: precise movements, a smile on her lips.

Her personal diary, covered in a hesitant and tight scrawl is filled with directives on the use of various weapons. On one page with schematic drawings, Sêal details the use of the RPG, how to load the rocket, arm it, shoulder the launcher… Technical explanations follow on ideological writings, leaving scarce opportunities for personal quotations chosen by the young girl – a few poems, whether composed by herself or not is unclear, honoring perhaps, two martyrs whose names appear at the top of the page.

Sêal’s diary: details on the use of the RPG rocket-launcher, May 2021

Tekoser 4

Another star shines in the sky, I know it is the spark from your eyes. I was never frightened by the dark nights but I was afraid of the spark in your eyes. It is so painful I cannot talk about it. I wanted to write your name in the legend of lovers, but I was afraid to lose you by writing it.

I am not afraid of this day, but I am afraid of the day when you will leave me all alone and go away. I am not afraid of death, and I am not afraid of the pain gnawing at at my heart, but I am afraid to lose you.

I am so fearful of your departure, that you will leave me alone in this madness, I am not afraid of the black nights but I am afraid to remain alone in them without you, no one sees this fear in my heart because I hide it from them.

My pain only hurts me, so why should I talk about it?

Do not make of your heart a river in which every passerby can drink, but make of it a kindgom owned by a rare person.

I regret no one who entered my life; the faithful ones made me joyful, the bad ones made me gain experience, and the best will never leave me.

Sêal had deeply changed. “Her mind had changed, her attitude, her language, she had started to talk like a kadro”, says her brother Reber – his name means “the guide”, one of the ways his partisans call Öcalan. He also fought in the YPG. Halima adds: “She was joyful, she joked, she told me ‘you’re bloated but my daddy is slim’. She was smart and everyone loved her, brilliant, she knew how to keep a secret. Thank God I am still and always proud of her.”

In her diary, Sêal wrote: “My Leader, you have ressuscitated the Kurdish people, you instructed it, you gave me a life with meaning and values.”

The family preciously keeps on a computer images of the young girl. On one video, she is seen sitting in front of a fire, head resting on one hand, thoughtful; beside her, a few of her comrades are dancing to music from a hand phone. On another video, she is leaving on a night operation, her head wrapped in two scarves. Her eyes are tired, her grave smile loses itself in the night. On the last photos of her, her features have hardened. Wrinkles have appeared around her eyes, despite her young age; she has gained in confidence. Many of her friends have fallen as martyrs. Only a few still show up to visit the family, such as her friend and first commander Ruken, now a driver with the YPJ.

As a child, Sêal liked to sit on the stone facing the oven and watch her mother prepare bread – May 2021

Girkê Legê, May 2021-09-30

The weather is stormy, the air is heavy.

At the exit from Girkê Legê, a small road runs next to derricks dancing their hypnotic dance near freshly harvested wheat fields. Heval Ruken’s home is by the side of this road. Her white Toyota pickup truck is parked in front of a wall surrounding a small courtyard. The house is painted white, the interior is cool. Small, lean, tanned skin and heavily marked features, Ruken is a kadro, a professional enlisted fighter. Like most of those who met her, she was impressed by Sêal. They met when she enlisted in the YPJ in 2013. There was a military checkpoint in their village. According to Ruken, seeing women in arms encouraged her to join them – plus, her brothers were already in the YPG…Sêal was the first in her village and its surroundings to join the YPJ.

Her thirst for learning, her curiosity and her charisma soon impressed the commander. She was first in her training class. “She was a girl from the Party.” Sêal was curious, constantly questioning the kadros about their life in the mountains in the PKK guerilla. She had books in hand, she wrote down her comrades’ memories, their stories. Although she had left school early, she still wrote in her diary. “She was unique”. During her year of political work, she met a number of kadros who told her “You seem to have spent years in the mountains.” But that work was not enough for Sêal; she wanted to be on the front lines.

A week before being killed, she wished to see her dear Ruken. The latter was absent and Sêal had come without forewarning. The two women had not seen one another in a long time, following three years spent together; Sêal had gone to the front lines, but Ruken hadn’t. She had seen combat in Tel Alo, Tel Hamis, Jazaa, Tel Temir, Heseke, in the mountains of Kezwan…

When she arrived on the front, she plunged straight into the universe of war. “Some fighters cried, morale was low, but heval Sêal wasn’t like them,” states Ruken. At the end of her training, she refused the ten-day leave. She did not want to go home, she asked to be sent to the combat zones – this was during the Tel Hamis operation, at the end of 2013. She liked meeting fighters trained in the PKK, those arrived from Turkey, Iran, Syria. And also, later, foreigners, American, French…“She was curious, talking about everything with them, fighting, friendship. She had a strong personality. Everyone appreciated her.” Despite the fact she was a newcomer, she was asked to train new recruits.

In 2016, she sustained a head wound during the operation to liberate the town of Shaddadi. An ISIS fighter exploded himself near the house where she was with her group and the house crashed down on them.

The village of Gir Ziyaret under a dust storm, in May 2021

“I can’t forget heval Sêal’s words when her cousin fell a martyr. She said: ‘Ruken, you must come for me, you are my darling, you have led me up to this point. Your friendship makes me stronger. If I die, don’t forget my family: bring a piece of fabric and a scarf to my mother.’ I said ‘I couldn’t do that, it would pain her mother’. It is painful when I visit her family, among Sêal’s friends, I am the one who remained. There are those who fell, those who married, those who left the YPJ, those who headed to the mountains. I recall our previous life, the kitchen, the watches. We were like two sisters. When we visited her home and she told her family ‘she is my commander,’ I said ‘we are friends, don’t use such words; we are the same age, we have slept together, we have gathered plants to cook them on a wood fire.’ So much so that the others passed comments. They told us to stop being together all the time. Such a strong link is poorly received here, but we couldn’t listen to them.”

On the way back, a storm hits the region.

A violent wind raises clouds of dust, the sky is tormented, low and grey. The light is odd, electric, giving the area a supernatural aspect. From the road, the village of Gir Ziyaret can hardly be distinguished, drowned in the dust.

Gir Ziyaret, May 2021-09-30

A few days after meeting Ruken, we pay a new visit to Sêal’s family. This time, her brother Lezgin is there, the one who is undoubtedly the post politicized member of the family. After time spent as a criminal investigaor in the Asayesh 5, he was wounded in combat in the Jazaa in 2014. Seven steel fragments are now embedded in his flesh. Today, he works coordinating with Russian forces.

“At home, she was quiet and kind, he recalls. I always say she was the one who most resembled our mother. When children fought, they called her Jackie Chan: no one could catch her at school! Newroz was brave and defended us.” On one occasion the brother ran across his sister on a theater of operations: she was in the front lines, he was in the back. “Following her enlistment, we didn’t see her often at home. She chose to sacrifice and to move away from normal, routine living. She was tied to the martyrs and to their roads. She wanted to live free. Jin jiyan e [woman is life]. This revolution forced us to take on responsibilities bigger than what we could handle.”

Sêal’s personal belongings – May 2021

He rises and goes for Sêal’s personal belonging – I had asked to see them, if possible. On my first visit, neither the mother nor the brother who was there at the time had mentioned their existence. Ruken is the one who talked about them. Carefully stashed away, they had slowly been forgotten.

Lezgin comes back holding a white plastic bag. Till that day, the family had not had the heart to open it – Lezgin only did so the day before our visit. Inside, a YPJ flag, an envelop, a bunch of notebooks and photos, one or two books, an Öcalan banner, a YPG crest. I start leafing through the notebooks. There are two kinds. Small ones with squared sheets and Öcalan’s portrait on the cover. These are filled with tight, tiny scrawls, the Arabic letters done in an awkward hand. These are Sêal’s notebooks. The others are a surprise: they are written in Turkish and a signature keeps on re-occurring, that of Arîn Mirkan.This captain has become a symbol of the battle of Kobanê by exploding herself in order to save her comrades. But the date doesn’t match. 2016. This is another Arîn Mirkan. In the end, a letter tucked in one of the notebooks provides the key to the mystery, a double page carefully written on a sheet of squared paper torn from a notebook.

This Arîn Mirkan’s birth name was Fatma Atkas. She was born in 1989 in the Mazıdağı district of Mardin province, in a family with no real militant sensibilities; she aspired to nothing other than a petit bourgeois existence. Fatma Atkaş studied at Siirt University to become a school teacher, before interrupting her studies in her third year. She met the PKK at the university. Began to take part in political activities and writing for the newspaper Azadiya Welat. Finally, in 2012, she joined the guerilla and trained in Qandil. For two years, she worked among the HPJ-YPK, the women’s armed forces linked to the PJAK, a sister-organization of the PKK fighting against the Iranian State. She was in charge of what she calls “civilian archives”. She then went back into training and was charged with training new recruits. But Fatma wanted to fight. At the tail end of 2015, she changed her code name and chose to call herself Arîn Mirkan. A tribute to the martyr, but also a self-directed message: she would carry on the struggle and intensify her commitment.

Shortly thereafter, in the first half of the year 2016, she finally obtained her assignment to Rojava to take part in the operation to recapture Manbidj and unify the cantons of Afrin and of Kobanê. The young women quickly became commander of a group of some thirty people and took part in the fighting. But things didn’t go as expected. Leading a mixed group was not a simple matter: for the first time, Arîn witnessed the death of one of her comrades; she was deeply affected. She asked to be sent to the front lines, which was denied her. During her self-criticism, the young woman pointed out her lack of experience which led her to be influenced in her decisions; she underlined the extent to which it was difficult to command men who do not always accept a woman’s authority, and apply practically the way of life proposed in the women’s movement, the PAJK. She ended with these words: “I understood how I had lost and failed and I am learning how to win. I think I am capable of being a PAJK fighter deserving the leader’s love. I will always be an uncompromising militant in fair comradeship”.

The letter is dated August 9 2016.

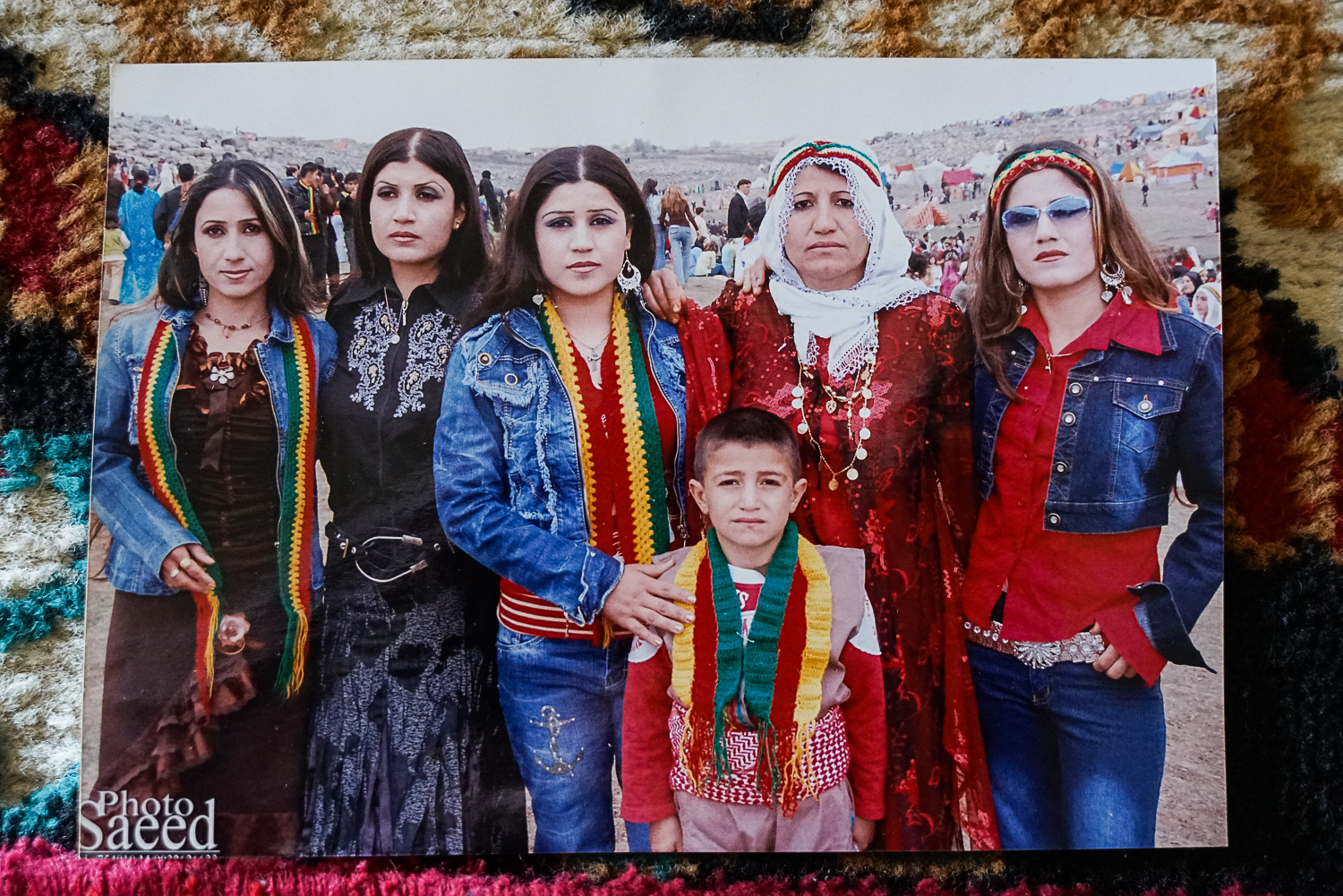

Sêal, on the right, during a Newroz celebration, in the early years of the 2010 decade.

Some eight months later, Arïn died in combat. Two days before the announcement of Sêal’s death, on April 5th, if one relies on the PYG’s official communications. Did Arîn confide her diaries to her before leaving on operation, as frequently happened? Were the two women close to one another? On a video undoubtedly recorded shortly before this, she is seen for a few seconds with Sêal as the two women seem to be preparing for a new night operation. On another video, they are cooking together. Arîn’s writings stop with this letter of August 9 2016. In a page of her diary, a few months earlier, she was already expressing the regret of having so little time to write. Sêal’s name is not mentioned, but perhaps the two women had not met yet. In any event, Sêal decided to keep Arîn’s diaries with her own. Perhaps with the thought of sending them on to her family some day.

Did she then leave for the fight with rage in her belly, with the thought of avenging the death of her comrade? She had seen so many of her friends fall, including her cousin Mazlum, the foster brother she loved so well, killed during the second operation on Tal Hamis in 2015. “The martyrs are our leaders, we will not move back, we will not kneel, we will resist” she had written in her diary, at an unknown date. Or did Arîn and Sêal fall side by side? The YPG do not always communicate all the deaths at the same time, in order to insure proper identification and communication to the families. Arîn’s death notice mentions the villages of Safsafah as the place of death; that of Sêal, Raqqa.

Derik cemetery of martyrs, in April 2018

The narration of military operations allows for a learer picture. In the night of March 21 to 22nd 2017, the battle to reclaim the town of Tabqa began, with the transportation by helicopter of American special forces and 500 fighers of the Syrian Democratic Forces (FDS) to the south of the town, to allow for its encircling. The fighting raged on, notably for the capture of a badly damaged damn threatening to rupture and drown the valley of the Euphrates. A brief cease-fire was ordered so that technicians could proceed to emergency repairs. The total encircling of Tabqa was achieved on April 5th and 6th 2017 when the FDS closed off the road leading to Raqqa by seizing Safsafah, a group of villages fifteen kilometers East of the town, on the shores of the Euphrates. The location takes its name from the Mediterranean willows that one finds there. Hundreds of olive trees grow there, and fields surround the village: a strategic location to keep ISIS from sending reinforcement to Tabqa.

The Jihadists had retrenched there. They knew their days were numbered and they fight fiercely. According to news sources, the fighting in Safsafah lasted close to forty hours, during which two journalists were wounded, ten suicide-attacks were repelled and eight vehicles loaded with explosives were destroyed. The ISIS fighters used the civilian population as human shields, complicating the task for the FDS who attempted to preserve the lives of the inhabitants and to evacuate as many of them as possible. Cornered, the Jihadists multiplied the suicide-attacks and mortar shellings.

Sêal’s family was told she had fallen into a trap. Ruken says the following: “They were six kadros comrades. Heval Sêal was the seventh. Normally, only kadros are on the front line, local fighters are in a supporting second line. But Sêal was with the kadros in the front line. The Jihadists set up a trap: two women and four of the male comrades were killed instantly. This was on the second or the third day of the operations.” In the publication announcing Sêal’s martyrdom, along with that of five other fighters, she is the only one whose place of death is indicated as “Rakka”. For the others who fell on April 5 to 7, the mention is that of the villages of Safsafah. In fact, the battle to liberate Raqqa only began on June 6 2017. In the press release announcing the death of Arîn, all the fighters have Turkish-sounding names which implies they were cadres trained in the PKK. And all were killed in Safsafah. Thus, it appears certain that Sêal also died there, even if it is hard to know if the two women died at the same time. Their different status, the one a PKK kadro, and the other a “local” YPJ fighter, may also explain why their deaths were not announced at the same time.

Tabqa was finally retaken on May 20 2017, after three and a half years under ISIS rule. According to a coalition general, the FDS lost some hundred fighters in the battle.

Sêal’s tomb, May 2021

Derik martyr’s cemetery, May 2021

Before her death, Sêal had started to glue into a spiral notebook photos of fighters she had known who had fallen as martyrs, along with dried flowers. Ronî, Harûn, Dersim, Têkoser, Mazlum, Sahîn, Rizgar…She wanted to tell their story. Now, she lies among them in the Martyrs’ cemetery in Derik, a few hours drive to the East of her native village.

In the clear morning light, the white marble tombs in the cemetery are lined up, all identical. They are decorated with greenery. On a few of them, flowers have been laid out; here and there, a scarf or a photo decorates one of them. It is early, the air is still cool. A few women, their faces wrapped in a scarf as protection against the sun that will soon turn scorching hot, clean the alleyways with water and see to the upkeep of the tombs. Lost among that of thousands of other fighters who fell for the freedom of their people, Sêal’s tomg is on the same row as those of the comrades who died by her side. To her left, Arjîn, then Arîn. 28, 22 and 23 years old.

A vast plain of cultivated fields spreads out around the cemetery. Green for a few weeks in the spring, it will quickly turn straw yellow. The Tigris runs there, oblivious to the borders imposed by Nation-States on the people who live there. Further back still, the massive shadow of the Cûdi mountains stand against the sky, the name Sêal had chosen for her second name – or the one that was assigned to her. It is on this mountain at the meeting point of three frontiers, Turkey, Syria and Irak, that the first Christians located the landing of Noah’s ark. Genesis will move it over to Mount Ararat, before the Coran finally brings it back on Cûdi. Today, those who lie at its feet are Muslims, Christians or atheists. Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians from the region or further off, who died defending, this one a land, that one his or her freedom, and another the ideal of a society with more justice.

Shehîd namirin ’ ”the martyrs don’t die”, chant millions of voices.

All photos by Loez.

Header photograph: Sêal, on Ronahi TV

Translation by Renée Lucie Bourges