Türkçe | Français | English

I will soon fall asleep. I will happily close my eyes and, if I’m still alive tomorrow, I will look upon the world with joy. I know now the value of sleep and joyful wakefulness in my twenty-five meter square home…

Today, for my eightieth birthday, I started playing by buying myself a cake. I smiled as I blew out the one candle I had put on it myself. Buying a cake and blowing out the candle, what a fine game it was for me…

There are many games I remember which I practiced until I was eighty years old, but none of them were a happiness game…

I lost my mother when I was four years old. She was buried in the cemetery facing our home. For a long time, I went to the cemetery almost every day, on my own. I always lied to my mother. I would tell her: “My father doesn’t beat on me.” I would say: “My math exam went well.” I would say : “I was selected for the school basketball team.” I would say: “The girl I fell in love with loved the poem I wrote for her.” I would say: “I’m studying at university.” I would say: “Military service doesn’t scare me.” While I was lying to my mother, an inner voice would say: “Your mother knows everything and goes on loving you the way you are…” I played games of tiredness, games of sadness with my mother… I learned my letters with you, mamma. We were a small harmony of vowels one for the other; your eyes were small, and so was my body. Your heart is not in a casket but always in my own heart.

I was six years old. Every weekend, my father would come home with a different woman, in the middle of the night. I would pretend I was sleeping. I heard my father’s voice and that of the women. The women laughed, their voices were joyful and, later, I could hear them moaning. I would cry silently and think of my mother. Those women were not happy. I understood that. Neither was my mother happy with my father. I understood that even better: my mother liked to sleep with me, not with my father ! My intuition was always wounded, at the age of six, I began playing with mutilated perceptions.

I was nine years old. One Sunday morning, I was at my maternal grandparents’ house. During breakfast, they told me: “Your father can’t take care of you anymore, and we are too old.” I kept silent. They said, “Your father’s family is very bad.” A shudder ran through me at that moment. “We spoke to your father, we are going to send you somewhere”, they told me. My knees began to shake. “A pleasant place, they said, you’ll have lots of friends.” “They will drop you off at school and pick you up there.” I lowered my head. “The food is very good and you will eat a breakfast every morning”, they said. “Can’t I stay here with you?” I dared ask in a low voice. “We no longer have the strength for it”, they answered.

From then on, I would dream in the bunk beds at the orphanage. Charlie Chaplin was my father, for instance, the rainbow I drew in my notebook was my grandmother and the moon, my grandfather. They loved me as much as my mother did. But just as she was not there for me, they were not there for me either. I considered love important, but not people. On a screen, just as in a theater of shadows, I found myself side by side with Charlot. This is what love looked like and at nine, I began playing with sad dreams.

I was ten years old when the dormitory director told me I would be “struck down” at the feast of sacrifice. I was the weakest of the class in mathematics. As if that were not enough, I was incapable of somersaults in gym, and each time I showed up for an oral exam, I couldn’t say a word. I answered correctly on written exams, but couldn’t say a single word at orals. There was supposed to be a punishment for that. That bastard was dead serious when he said I would be “struck down” on the feast day which was the the next one. I talked about it with my friends in the dormitory. They had been told the same thing. “We are going to cut your throat and be rid of you!” No one was able to sleep alone in his bed, that night. We slept three to a bed, holding on to one another. Each of us suffered the same pain, our throats were burning. None of us were “our parents’ lamb”, oh, how can I explain this to you… On the morning of the Aïd, this man lined us up in front of him and said: “Be grateful to our State, I convinced the authorities, even though it was difficult, you will not be struck down !” At the age of ten, my games were broken and, when I looked at lambs, I didn’t see meat, I only saw life…

At the age of thirteen, I fell in love with a girl in my class. With a trembling voice, I told her of my love for her. “Two other boys are in love with me. You will all write me a poem, I will go out with the one whose poem I’ll like the most.” I though about this for a moment: “Why should a be part of a contest?” I said to myself: “What need is there for this?” But I loved this girl a lot. Once everyone had fallen asleep in the dormitory, under the blanket with a flashlight in hand, I wrote what follows on lined paper.

Ô thou whose face is my day star

I am not the kerchief on your head

Nor fate in your life

Let me be the perfume of roses

In the palm of your hand…

The following day, with shame and embarrassment, I gave her my poem in an envelope. She said: “Don’t go away, I want to read it right away.” I was happy, very happy… She opened the enveloped. “You wrote it on lined paper,” she said in an arrogant voice, and she started to read the poem out loud. “Am I your ’face of the day star”? She said, laughing. “Yes,” I answered. She showed me two other poems that she pulled out of her satchel. “Look, she said, in one poem it is written that I will be adored like a goddess , in the other, that he would die for me. What would you do for me?” “The perfume of roses, I said, I want to be the perfume of roses in the palm of your hand…” “Who are you to understand anything about love” she replied with a pout. “What do you understand about love?” I answered, “what can you do for the one you love?” “For as long as he venerated me, and dies for me, I will do everything,” she said. “Love makes you live, I said, love makes you live a thousand lives with enthusiasm, full, colorful lives…” A cyical look then appeared on your face. At thirteen, I was playing dangerous games…

I started smoking at the age of fifteen. I was still the weakest of my class in math, I still couldn’t manage a backward somersault and I was rejected by the girls I loved. No one came to visit me. My father didn’t care about me. The State was our father, we were told. One day, I saw an old dog wandering in the school yard. He came close to me and crouched down. I started to pet him. He looked me in the eyes, quietly. I said: “Papa”, and he gave me a paw. I started sobbing. We began speaking to one another in an unknown language. “I miss my son”, he told me. “I asked: “Where is he?” He said: “He is dead.” I asked: “Why?” He answered: “Street cats and dogs die young, generally speaking.” I said: “Will I die young?” He said: “You will live. I will be your father and a young life will bring you happiness at the end of your life.” My friends came to see me. “A cigarette, I said, give me a cigarette”… I smoked my first cigarette while petting the head of the stray dog who was treating me like a son. At fifteen, I played with a lot of old street dogs, games filled with tears and cigarette butts…

At seventeen, I chose to study, not in a university but in the sky, for instance. At eighteen, I was expelled from the boarding school and didn’t take on any of the jobs the State found for me. All my friends considered the State to be their father whereas, for me, dogs were my father! My first job consisted of selling balloons. Children would come to see me, holding their parents by the hand. I was happy to see the children, happy, peaceful and safe. I lived in the lodge of a janitor, with four other people. This time, not in a dormitory but in a janitor’s lodge, I played at writing poems.

Open your hand

Like a tired love poem

My voice is about to break

Out on your narrow lifeline

On which I distilled so much hope

It will stretch out its full length

Open your hand…

When I was twenty, I served my country in the army. The earth was my country, nature, the universe and also my heart. No one knew this. Talking to the flowers, for instance, this was a patriotic duty, just as confiding their names to streams and stars were. I was afraid when I was in the army, and I never pretended to be first on the firing range, as others did, I never claimed to be the fastest runner, or proudly stated I was never cold, even at minus fifteen degrees ! My heart was my country, and my heart was alone, very much alone. One day, I said: “bedding, bed, water and humanity”. “We are alone, comrades” I said, beginning a song. Neither of us was able to finish it. Tears came to our eyes, the both of us…My games of solitude increased during my military service, at age twenty…

I never married, I didn’t believe in marriage. I would go to orphanages on weekends, I considered the children as if they were my own. Even when they cursed me, they were my own children. I also wrote poem for the children.

The child

One day, when he didn’t find a friend to play with

For the first time he called to his side

The god he thought to be alone as he was

With his hands full of marbles

With his voice so damp and quavering…

For years, I played with my indecision, with evaporated poems, with grumpy children, with the lights filtering through light bulbs, with houses that were never bigger than a janitor’s lodge, with the fragilities of doves, and with my tired hopes. I aged while playing with my wounded hopes…

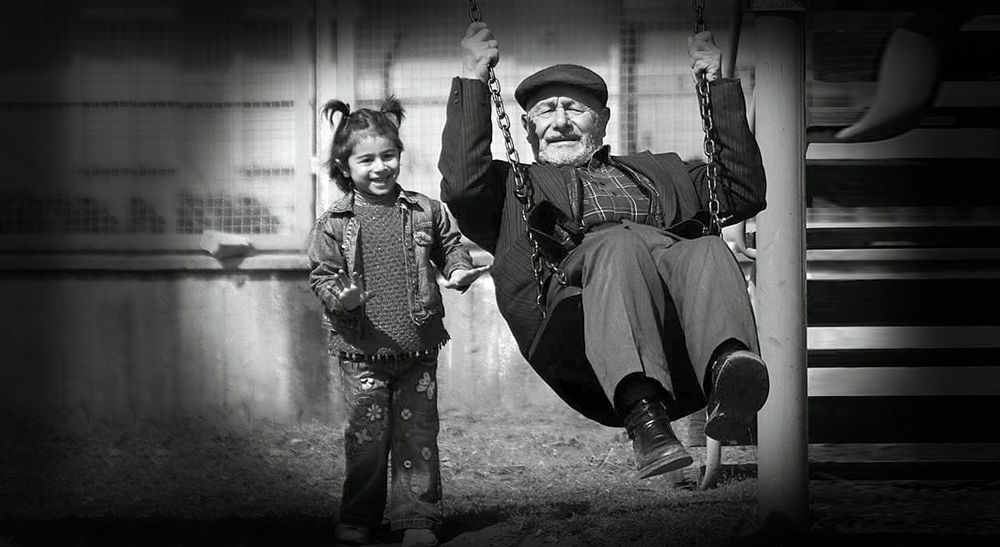

Today, as I was sitting in the children’s garden, a little girl approached me.

She said: “Uncle, how old are you?” I answered: “Eighty years old.” And she asked me: “When is your birthday?” I couldn’t remember, all of a sudden. “Wait, my daughter, I said, let me check.” I pulled out my ID, looked at it and said: “It’s today.” “Come, she said, I will give you a gift.” Before me, her parents, a pair of smiling hearts. I got up from the bench , she took my hand and led me to the swing. “Sit on the swing, uncle.” I sat and she said: “I’m going to push you”, and I smiled. A tiny little girl pushed me on a swing on the the day of my eightieth birthday. Tears filled my eyes. “Don’t cry, uncle, she said, today is your birthday…”

Many stray dogs, pine needles and pebbles had adopted me, but for the first time, a little girl was looking at me, eyes filled with sincerity. “I will buy you a gift when I have some money, but buy yourself a gift today.” “I promise, I told her, I will buy myself a gift…”

I celebrated my birthday for the firs time on the day I turned eighty. As I was wondering what gift to buy myself, the stray dog with whom I had talked when I was fifteen reappeared before my eyes. “Oh my son, he said, my beloved son, you have never eaten a cake properly, buy yourself a cake…”

So I began to play today, on the day of my eightieth birthday, by buying myself a cake. I smiled as I blew out the only candle I had put on it. Buying a cake and blowing on candles, what a fine game for me…

I was always fated for happy games, I learned this on the day of my eightieth birthday

Translation from French by Renée Lucie Bourges

Support Kedistan, MAKE A CONTRIBUTION.

We maintain the “Kedistan tool” as well as its archives. We are fiercely committed to it remaining free of charge, devoid of advertising and with ease of consultation for our readers, even if this has a financial costs, covered up till now by financial contributions (all the authors at Kedistan work on a volunteer basis).

You may use and share Kedistan’s articles and translations, specifying the source and adding a link in order to respect the writer(s) and translator(s) work. Thank you.