English | Français | Castellano | Kurdî | Türkçe

Zehra Doğan, presently incarcerated in the Type E penitentiary of Mardin, wrote a letter to JINHA, the news agency of which she is an editor. She describes prisons as places of resistance.

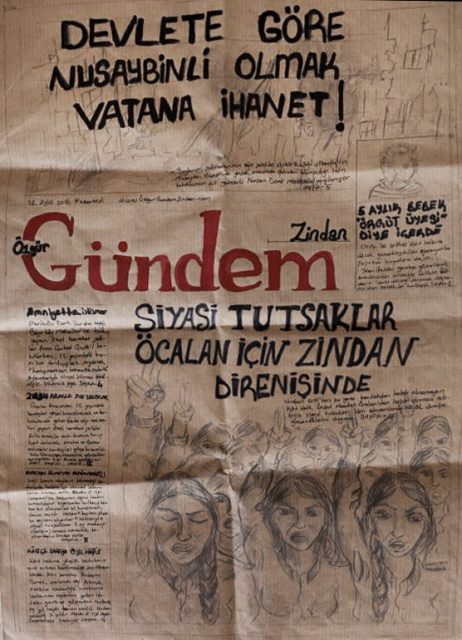

Zehra uses both her drawings and her reportages to inform international public opinion of the realities of months of State attacks against Nusaybin. A short while ago, she rose up agains the closing of the newspaper Özgür Gündem by publishing “Özgür Gündem — Jail” with her co-detainees. In this latest letter to JINHA, Zehra describes the changes she has been through since her arrival in prison and the emergence of the concept of “Özgür Gündem- Jail”.

Here is her letter:

Dear JINHA,

I woke up far from all of you for another day in jail today, which is a place of great comradeship. This town where the wind carries the arid dust of Mardin, rich with its historical past, is a place favorable to dreaming. It is the birth town of Mani (Editor’s note: prophet, founder of manicheism), who travelled across the land to teach the truth, and who spread his message through his canvasses. It is also the city of Shahmeran [Editor’s Note : the snake queen, a legendary figure) who, according to some legends, possessed wisdom. Being here, even as a prisoner, gives me strength.

Yes, being held captive in my own land is hard for me, but as soon as I entered here, I found myself surrounded by 45 women filled with wisdom, women who have become goddesses. When I saw the spark in their eyes, I understood that the most important space for the struggle is this one, pressed in between four walls. Once I understood that each one of the women with whom I spoke held in her heart a formidable history of struggle, I was able to draw strength from them. During my first prison stay, I was crushed at being so far from my work and from JINHA, then I realized that this was the place where the most important news was happening. This is where a journalist must be, to inform the public of each injustice committed here. Who knows, maybe that is why I’m here.

During the interrogation following my arrest, the interrogators kept asking me, with their masculine mentality: “Why do you do this work? Why do you cover the news? Why do you draw?” In fact, when we began our work at JINHA, the heiress of women’s resistance, we took up our pens with this cry: “we will write without thinking about what men will say about it”. And while we were writing, we learned that “when women begin to write, the image of the men in the mirror starts to fade”. This is why I felt no need to answer them. Even behind iron bars, they couldn not take away my best weapon against the oppressors: my pen and my paintbrush. I’m aware of the fact I have a right to them thanks to the sacrifices of many wise persons before me, and I know I can’t easily be deprived of this right. I don’t feel isolated from society, nor from JINHA. Quite the opposite, I see myself now as a prison reporter for JINHA, and this makes me feel proud. We constitute the media arm of the women’s struggle for our freedom, and that is why prison is one of our main battle fields. “A free life must be an infinite reality.” And I think that this is where I can best see this infinite reality.

I see a jail holding so many wise people as a great school of thought. During my incarceration, in particular, I realized how important my profession is.

Everyone was enthused by this idea and we set to work immediately. There were many prisoners here whose treatment had to be revealed, who had been subjected to various tortures and violations of their rights. The best way to make prison reality known was to publish a newspaper. We worked days and nights to create the Özgür Gündem in prison and to fight for this paper. We continue to do so on a regular basis. We have neither computer nor printing press, but we have ballpoints and paper. We have no cameras to photograph the people we write about, but we are also artists. What we can’t photograph, we can draw. The more I wrote and the more I drew, the more people talked to me. At first, I was the only one working on this newspaper. On the very day when it was transcribed onto paper, the iron doors of prison opened. Another journalist, Şerife Oruç, joined us. When we most needed her, she came to us. We have a newspaper. Perhaps several people have read it by now.

Today, there are a number of journalists in our sections. Several of our friends have trained to become reporters and write for Özgür Gündem in prison. I also give drawing lessons twice a week so they may illustrate the news. Recently, we began preparing an art exhibit, the benefits of which will go for support to the self-managed zones. We spend more time on this than we do on imprisonment.

All our friends have the spirit of “Apê Musa’s little generals” [Editor’s note : Kurdish children who distributed newspapers forbidden, censored or seized by the government.) It is said that “Since human salvation doesn not come from God, it must be found on earth.” This is why we attempt to turn prisons into places of struggle. Perhaps I will never be liberated, this is Turkey after all. I don’t realy expect this to end well.

I know that, with women’s resistance techniques discovered thanks to JINHA, I will destroy prisons with my pen and my paintbrush. Don’t forget that the pen and the paintbrush are still in my hands.

I miss you and embrace all of you.

Zehra

Number II even reached students at Dicle University

A campaign of support is presently underway: Send solidarity postcards to Zehra Dogan.

You can see Zehra’s drawings in our article: Zehra draws the unspeakable. (In French)

And here are a few original drawings from the women’s prison in Mardin…

Illustration: “this is a very dangerous weapon”

Letter published by JINHA.