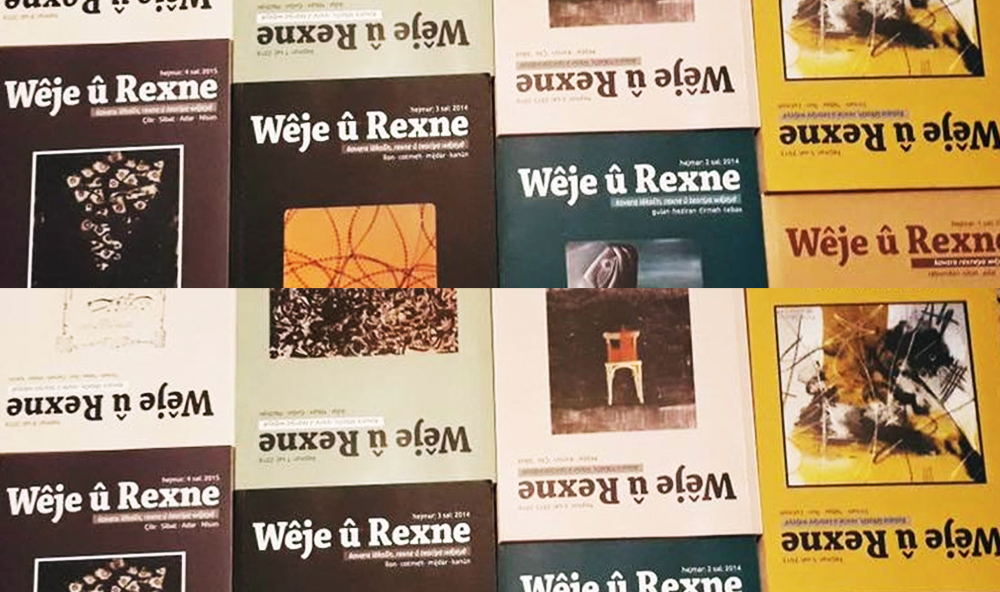

Investigating new forms of writing about reality, Serdar Ay, editor of the Kurdish magazine Wêje û Rexne (Literature and Criticism) and Fanch Ar Kazetenner conducted an interview with writer Joseph Andras. Here is a version in English:

Wêje û Rexne : Twitter @wejeurexne | Facebook.

Your most recent book has just been published. You examine a little known figure of the French Revolution, Camille Desmoulins. Pour nous combattre (To fight against you): isn’t this almost a title for a political program in the current context?

I examine the creation of a newspaper Le Vieux Cordelier. Therefore I look at its author, its readers, its supporters and its opponents. Desmoulins is but one of the many characters in what I consider above all as a fresco, a collective composition. But you are right: the title aims at addressing something to our times. It is part of a verse in La Marseillaise (the French national anthem). This book provides precise facts, of course — averred, dated, documented, sometimes vastly commented over three centuries. But above all, there is mostly the friendship, the dissensus, the compromise, the coherence, the purity, the violence, the law, faith, morality, realism, strategy, efficiency and cynicism. There is the vanguard, the masses, the people, classes, the State, intellectuals and power. What drives, affects and mobilizes these revolutionaries is not exhausted solely in the historical relating of events. And there are also these two notions structuring the whole of the book: that of the Revolution and that of the Republic. If my interest in this period is long standing, the writing owes much to our current “republican” atmosphere. To its unbreathable air. One might even say that Pour vous combattre is a line-by-line dialogue with our present context, as you call it. Fighting against the current “republican” force, while fighting internally what led toward our failure. This dual movement winds its way through the entire text.

In 2016, you refused the prize attributed to your novel De nos frères blessés (Of our wounded brothers) by the Académie Goncourt, one of the most prestigious prizes in France. “Competition, and rivalry are foreign notions in my eyes to writing and to creation” you indicated.This raises interesting reflections from the point of view of the situation of literatures from dominated countries and minorized languages. For example, because of humiliation and stigmatization bringing on a sort of inferiority complex, the writer goes in search of recognition — to such an extent that he often finds himself creating a fetish out of the writer and literature. In the opposite case, in order to “decolonize the mind”, some feel the obligation to come out from behind the words they used as a hiding place in order to make some “noise” that will strike against the silence and the deafness to which they are subjected, in order to “invent a people” (in the meaning attributed to the words by Deleuze), in order to “emerge out of the great night”. Because most of the persons in this people of the great night do not know their maternal language in writing. What do you think about this?

I can’t answer you concerning dominated languages and territories since my maternal language is French and that I do not know in my own being what it means to be a minority. Except politically, but that is in an entirely different register. I understand the psychological, social and political mechanisms at work in the desire for recognition, in the search for validation and legitimacy, in the search of ratification by already consecrated instances. I know that I can incur the objection to the position I defend: refusing, means having the luxury of doing so. My position stands on two legs, in fact. One being political and the other, internal working out of issues. The 20th century left us the legacy of an idea I attempt to appropriate — let us say, more than that century, the revolutionary union work in its midst: the “refusal to achieve”. Behind this, we find people such as Albert Thierry and Marcel Martinet. “For as long as our triumph will not be at the same time that of everyone, let’s have the chance of never succeeding!” Elisée Reclus said before them. The communard (a figure of the Paris Commune of 1870). I am paraphrasing him in fact, without naming him, in the overture of Au loin le ciel du Sud (The southern sky in the distance). It is a refusal both individual and collective of the the rules edicted by those in the world above. Your decorations, your approval, the coordinates of your social order do not concern us. There is some of that. And also something much more basic, so basic that I’m not too sure how to formulate it without embarrassment: I have a spontaneously anarchic relationship to institutions, to honorability, to podiums. But saying “anarchic” already supposes an a posteriori ordering. It politicizes a feeling, an intuition, a way of being over which I have no control — character, as they say. But I would like not to be talked to about this refusal any more. That is to say, that it be perceived as a norm. That no one ask me anymore why one refuses podiums, but rather why one agrees to stand on them. That we reach a collective agreement that the artistic does not enter in categories of competition. We are far removed from this. One only needs to count the people who, at the time, considered the letter to which you refer, rather than as a mark of distinction as who-knows-what calculated maneuvering. Well and good: as always, the rotten ones project on others the rot that constitutes their person.

You who never show your face, use the image of your main characters as covers on two of your books. Can this be explained by the meaning you ascribe to what is common or by the will to bring to light these forgotten vanquished ones, in order to “feed anger against the guilty” as you have said?

It is purely anecdotal, not to say ridiculous, but my “face” is visible by anyone who would have the odd idea of being curious about it — on internet or in the media. I uphold a rather rustic notion: that I write, therefore, what matters is what I write. I wonder why one expects a writer to exhibit anything other than that for which he is fashioned: piling up syllables on paper. That being given, one can indeed see on the covers of De nos frères blessés and of Kanaky, portraits of Fernand Iveton and Alphone Dianou. I approach this personalization in a dialecdtical manner — if you’ll forgive me the fancy word. One, it answers the biographical perspective of these two texts; two, it constitutes a dialogue with the title. Two titles resolutely collective: “our brother” and the name — voluntarily left unuttered — of a country. This combination allowed me an answer to this tension, this knot, if not to say this most classical of dilemna whenever one moves into the political sphere; how to articulate the individual and the collective? At what moment does one fall into heroization? Into the myth of the “great man”? In a reading of History that would trample the numerous and their upsurges? At the opposite end, on the contrary, at what moment does one crush all individual and subjective perspective in the sole name of the group and of the masses? Placing a figure — unique, by definition — and titling in the plural was the way I found in order not to sacrifice anything.

In De nos frères blessés, one reads “Death is one thing, but humiliation inserts itself under the skin, it implants its tiny seeds of anger, and destroys entire generations”. How doe one proceed to de-humiliating the spirit?

It’s a difficult question. And I’m not certain that I’m the person in the best position to answer . What I understand politically on the topic, I owe to others — which is to say to those who, personally, in their family, have experienced and related social, political, memorial humiliation. The sentence you quote refers to colonial trauma. In an almost clinical, psycho-analytical sense. We are familiar with the many answers formulated by heirs to this story: the rehabilitation of a past either hidden or destroyed, reappropriation of dishonored signifiers, demands for symbolic or financial, reparations, debt forgiveness, struggle here and now against the concrete repercussions from this past. In France, it appears to me that the heirs to colonial history and immigration call for nothing other than “justice, truth and dignity”. They call for equality and that only this equality will allow breaking the chain of humiliation or of a deficit in consideration. Clearly, only imperialists speak of “repentance”. What I can do in this matter, is support these struggles, inasmuch as I can, and, as a writer, a purveyor of tales, “write while listening”. I’m using here writer and journalist John Gibler’s expression. Meaning to avoid engulfing — I’m thinking specifically of the kanak issue — the witnesses and actors’ discourse. Insisting on resistance practices at the people’s level. Re-directing the critical eye toward those in power, to power’s structures as well as to its agents. One shouldn’t attempt to awaken the reader’s compassion but rather blow on its embers. There are victims, this is obvious, but leaving the reader alone with them, face to face in a glaring light, seems inoperative to me. It paralyzes, it weighs down, it inhibits, it afflicts, it turns inward, in short, it dis-empowers Exposing refusals and designating the organized supporters of inequality, provides other affects. It sketches a possible response. Or, at the very least, and this is already not so bad, it maintains afloat the very notion of a response.

In your writings, violence occupies an important space, between humans through colonial violence, as well as toward animals. How do you envisage this question of violence ?

“Violence”, is always the visible physical violence emanating from below. Union members tear off the shirt of an Air France executive, Yellow Vests throw up barricades in front of shattered windows of luxury boutiques, PKK fighters hit upon some barracks, activists mistreat hunting installations. But there is a choice involved in using the word “violence” to speak of this — and to speak of nothing else. An editorial, media, political and ideological choice. Reason for which most of my books suggest a shift. A time interval. They take a step back upstream. They take a look at the foundations, the way an archeologist searches the ground. Taking into account only the topics I have covered: Fernand Iveton wanted to sabotage material, Alphonse Dianou and his comrades were held hostage by gendarmes, Hô Chi Minh became a war chief and the Animal Liberation Front destroyed a scientific research laboratory. All of them were described by the powerful and their journalistic henchmen as “violent” and “terrorists”. Yet there is rarely any mention of the violence that awoke “the violence”. Of State terror, of legal terror, of parliamentary terror, of terror in times of “peace”. The tale is truncated to the extent of producing something other out of it: the last chapter becomes the start of the story. Thus, there is “violence” that is formulated, that is described as such: the dispossed suddenly turning on the owners; the exploited who, one day, say “stop, that’s enough”. And there is the violence that is never put into words. The workers at the Knorr factory in Duppigheim were fired in 2021 following delocalization of production to Romania and Poland. But that is not considered as violent. It’s “a reorganization of expertise centers”. A Frenchman with low revenues does not live for as long as does an upper-level executive in the same country and a fairly recent study from the Labor Ministry indicated that “with comparable qualities”, Arab job seekers had 31,5% less chances of being contacted by recruiters: that is not violent. Léa Salamé and Nicolas Demorand (media figures) don’t call on anyone to “condemn” those violences. Because that’s the world as it is. On Europe 1, all will agree that work-related accidents are “sad”, but the sadness does not call for anything further. I could multiply the examples. Going upstream in the river, in this way, and bringing to light the violence of which we are told it is no such thing: that is what I have wanted to do.

You are wary of the aesthetics of defeat as well as of revolutionary intoxication. You bring up those who were swept aways, crushed, erased by the History (of the dominators). Through their “memory”, what “reality” (as a means of projection into the future) are you attempting to show or to build?

My undertaking is based on a dual urge. First of all, providing my small share to the reformulation of History and, by this, sharpening our memory. I am far from being alone in this business. Who remembered Iveton outside the circles of historians and militants? Who had heard of Lizzy Lind af Hageby and her accomplice? Who knew the life of Alphonse Dianou? Since New-Caledonia is still French, Dianou is a French citizen de jure: he headed an action that upset the political game over there — hence over here also, in one way or another. In the strictest meaning of the term, he cut History in half. What I am about to say is less secondary than it may first appear: Dianou has no existence on Wikipédia — an encyclopedia the weight of which everyone is familiar when it comes to the daily spread of knowledge. History — which is to say the saga of the powerful — hands out the positioning and delivers the good marks. Last year, Macron carried out an “enlightened commemoration” in favor of Napoleon: try doing the same with Robespierre! Yet this is a figure much less barbarous than the first. Even Napoleon admitted they had laid it on thick in his case. Secondly, I take to heart Victor Serge’s invitation to follow “the rule of the double duty”. Fighting against the enemy while carrying out the struggle in our own ranks. Or, at least, according to the times and the circumstances, while keeping my eyes wide open. This is how I would like to contribute to drawing attention to the refusals of the forgotten and the uncounted, without contradiction; saluting the losers in the eyes of what the masters call success: honoring the losers among the losers, by which I mean those that ours have sacrificed once they managed to attain power. I do not self-define as a Trotskyst but the Trotskyst gesture is familiar to me. I know well this tradition of repression, exile and of plural fronts. We return here to Serge and his revolutionary opposition to “revolutionary conformism”. We could also mention the anarchists: the forever beaten. The great sacrificed ones. This was the central question of my book on Hô Chi Minh. It is the crucial one in Pour vous combattre. I know, notably in the most libertarian minded ones, the respect given to the defeated ones, to failures, to martyrs, to the magnificent losers. I know this that much more clearly that I have somewhere in me something of this inclination. But I struggle with it. It is easier to love Jesus than Saint-Just, Rosa Luxemburg than Lenin, Makhno than Castro, Vallès than Chavez. I could sign off on every word of the “leftist melancholy” historian Enzo Traverso mentions. Simply remain aware of complacency. Of a leaning toward dandyism. Of the literary style. Because I wish to witness the defeat of the enemy, its debacle in the field. I would like us to manage in breaking all the structures of subjection, one by one. True, we are walking through the ruins: the crimes of the Stalinists and of the social-democrats, but yesterday’s corpses must not block off all of the horizon. I attempt then to live in this tension: let’s try. We will fail, undoubtedly. Certainly, even. Then, we will have to try again. It will always be that much snatched away from the moneyed class, from the forces of the unjust. The revolutionaries of 1789 held out for two years at the head of the Republic, after which they killed one another in conditions that continue to affect me. No matter. For over 230 years, we have lived on what that handful of years made possible by smashing doors and windows. Starting with the democratic possibility. A trifle…

You gladly “dig into the poets’ bag”, borrowing their tools. What space is reserved to orality in your writing?

A space that may appear as paradoxical. By which I mean that my texts are very “written”. Comma after comma. What is owed to randomness is only called the unconscious. Everything is knitted, framed, weighed. In this sense, my writing is at the opposite end of a certain written “oral” tradition, of a tongue that flows, improvised, automatic or dialogued. What calls to me are the rhythmical potentials and the reserves of poetry in prose, its share of singing. They are what allow me to spend so much time glued to my table. But orality is essential to me, musically speaking. Like many authors, I often compose out loud. The melodic line provides the direction. My relationship with poetry can probably also be found in a certain taste for brevity and condensation. In the fact of sharpening the pencil to a point.

You have trouble writing at length?

Yes. I struggle. I have natural difficulties in diluting a point — just as, in daily life, I have trouble following wordy, diffuse discussions. I never tell myself that my books must be brief: once they are done, I see that they are so. Without wishing it or aiming for it, I see in this a call to poetry. And to song — that I do not set apart, in fact. I don’t know if there would have been a S’il ne restait qu’un chien without Brel’s song “Amsterdam”, for example. That relationship to poetry, is also a matter of companionship. There is nothing of the erudite in me in this matter: my knowledge is straggly, incomplete, fragmentary. But in the end, yes, poets feed me as much as prose writers do. It could be a presence, an image, a certain color. Before writing a page, it may happen that I will open a collection by Khaïr-Eddine for example, to catch a tone, a note. When Lorand Gaspar writes “the sun cut itself out slowly/the way my mother cut the bread”, I can’t see how prose could ignore that. Or if it does, almost always, boredom takes over. A “literary” language devoid of bumps, with nos jumps and without music, I find complicated to follow. In S’il ne restait qu’un chien, we come across Cendrars and I had Fondane’s Ulysses in a corner of my mind — we come across it often in fact in Au loin le ciel du Sud. I take a few words from Rimbaud, without quotation marks, in Ainsi nous leur faisons la guerre. There is some Mayakovsky and some Pasolini in Au loin — I do believer there was also some Nâzım Hikmet but it ran off the pages. He will return, somewhere else, one day or another!

You base your writing on investigative materials you gather yourself in an approach resembling that of an investigator, a journalist, a historian. What connections to you make between the writing involved in journalism and in literature? How can these two forms of writing nourish one another?

Everything fits together without difficulty. I am not a historian but I spend my time with historians. I am not a journalist but I closely observe the news and am interested in the conditions of media production. I never set foot in a university but I read as much human and social sciences as I do literature. When the moment comes to write, these various tools and means of expression show up or conflate seamlessly. It is a palette with several colors at my disposal.

In Ainsi nous leur faisons la guerre, you question the “relationship” between human and the living non-human around the topic of the public vivisection of a dog in London in the very beginning of the 20th century, the kidnapping of a baby monkey rendered blind in a Californian research lab in 1985 and the escape of a cow and her calf, who broke away from a transport on the turnabout of Charleville-Mézières in 2014. What must be done in order to go “toward an ecology of the narrative”, meaning raising the problem of humanity in the “City”, in modern literature, and moving toward a literature of a humanity on a “Planet”?

I don’t use the “ecology of the narrative” expression but I think I know what it deals with. In truth, all I do is prolong in literature — and more particularly in the book you mention — my own relationship with the world of the living. Animals matter in my life; they find themselves at the heart of my texts for this reason. I do not disconnect animals from humans. This would be a scientific aberration, at any rate. The relationship we establish with animals is closely linked to that we establish amongst ourselves, where the “we”, as we know it, is widely heterogeneous and conflicted. In the long march toward emancipation, we will not be able to make the economy of a reflection on the fate we reserve to animals. We cannot work at the diminishing of violence in social relationships while silently wading in the blood of others. But what I’m stating is evident: I’m simply following in the footsteps of the revolutionaries, the feminists, the environmentalists, ethologists or anthropologists who, for a long time, have refused to crown Homo sapiens as the Earth’s Grand Sovereign. There is no airtightness in politics. No scattered “causes”. I believe there is never anything other than continuum and combinations. The regime of inequality is made of a ball of hundreds of different threads. A skein. This does not mean that this mobilization or that one cannot demand autonomy — but by the nature of things, this autonomy can only a relative.

The Kurdish writer is sometimes blocked by the intensity of reality when writing fiction, which requires removing one’s self from the “context” or the “reality” affecting him or her on a permanent basis. “Kurds live their novel, it is impossible write at that level”, they say. What are your thoughts on the literature of those times when one believes he or she has captured “the breath of History” and the “literature of extreme situations”? How to pull back from the “climate” so as not to neutralize critical thinking?

Except for De nos frères blessés, I have not written any fiction. And even there, it was a bastard-fiction — very largely resting on facts and documents. Today, which is to say six or seven yrars later, I would not write this book in the same way. I rarely go back on my texts, but Pour vous combattre is much closer to me, organic — in terms of a capture of History, of narrative policy, of structuring of the narrative. Undoubtedly, I had not perceived this immediately, but I am wary of historical literature one could call “entomological”. Looking at the trenches, the Paris Commune, or, I don’t know, the Spanish war, the way one would look at a butterfly nailed to a frame. No one can deny there exists a literary aura to the past. A heightened romanesque and lyrical possibility. Rebellion enchants everyone when it doesn’t cost anything: it can even become the object of a visit to a museum. Of course, one can relate by taking hold of the past in order to allow the reader to draw “lessons” from it. This is convenient. Humanistic. To put it in other words, I fear a historical literature in which the displayed radicalism has no bearing on our time. I approach History in order to rub up against it in a single movement, with the masters of the moment. I’m quite certain I would be unable to write a book on nazism: I feel the need to take the blows. When Valeurs actuelles [French right-wing magazine] tells me I’m glorifying a terrorist and Le Monde [French newspaper] says I’m Manichean, I have the particularly pleasant feeling of a job well done. In speaking, I suddenly recall a comment concerning Au loin le ciel du Sud: someone telling me they loved Nguyên Ai Quôc’s initiation tale but nothing about the Yellow Vest insurrection in the streets of Paris which I relate. That’s not how it works: it’s all or nothing.

Several researches show that literature is seeing imposing extensions these days: “From a literature defined by its disinterest, its autonomy, to contemporary writings willingly social and political, from the crowning of the author to amateurs of fanfictions, from the unique preoccupation with style to non-fiction, from the apology of originality to the required investigation, from the solitude of the creator to field literatures, from romanesque novels to writings about non-human worlds, from the cult of the text to writings outside books, from the Western tropism to world literature, from a linguistic concept to an approach informed by cultural anthropology and nature sciences.” From this, how do you see the new dynamics in literature written in the French language? What space to you think you occupy in this new literary landscape?

I’m not terribly knowledgeable in matters of literature studies and theories. I catch on to the branches as I fly by. As for my place, this is a matter for others to say: I only have two or three ideas about the position I build. I absolutely do not see books as unique entities, self-enclosed, susceptible of being received and understood separately: they are elements, assembled in various ways, of a work site of which I am ignorant, of course, of the shapes it will take on. But my bit consists of the junction between literature, hence art, and politics. How to occupy this space without falling into socialist realism or decorative marginality, in the “culture mode”? How to grasp formal research and readability? How to set up a discussion between song and usage? How to move, to compose between those two poles, externally and in themselves? It’s an ongoing reflection. “In me, the poet fights the militant and the militant fights the poet”, Kateb Yacine said in a book of interviews. He was speaking of an “unavoidable” civil war. From the onset, I’ve had the feeling I must not take my eyes off these two struggles.

If, far from being an essence, literature is first of all an idea, what is literature for you?

I’m still wondering how one can answer this question, after the hundred illustrious definitions already pronounced! Following Sartre, obviously. So, all things considered, I offer these commonplace words: I consider literature as the affecting and aesthetic part of prosaic language.

You dedicate one of your recent works to the imprisoned Kurdish singer Nûdem Durak. What is your relationship with this singer and more generally, with the Kurdish people?

As a general category, the Kurds don’t evoke much for me. No more than do Palestinians, Algerians, Vietnamese, Russians or French people. My internationalist links are first and foremost political, ideological. What I can say, on the other hand, is that in my political tradition, I , like many others, hold in greatest esteem the social, democratic, socialist, feminist or revolutionary Kurdish movement. It is among my friendships and inspirations. As for Nûdem Durak, I went to Kurdistan in order to meet her family. I will go back again. She was sentenced to nineteen years in prison for her involvement. But a political prisoner is never an isolated individual: that, again, is a matter of how the system is constituted.

Translation from French by Renée Lucie Bourges

Support Kedistan, MAKE A CONTRIBUTION.