Türkçe | Français | English

Simply put, exile is an adventure in beginning one’s life anew. It may be an attempt at laying down roots in other lands, under a different climate. Your roots having been confiscated, it certainly will not be easy, but you have to start somewhere.

When I started asking women who had been exiled from Turkey questions that concerned me, as a woman in exile myself, I had the idea of turning their answers into a series of articles. So I started writing. How do these experiences of the oppressed turn into knowledge for the benefit of the newly exiled women as they go through their lives?

I would like to start with Şengül Köker

So I knock on eldest sister Şengül’s door. This time, I ask her to translate exile and talk to us about it. “How did your exile begin, big sister Şengül?” I ask. And she begins the tale…

“How long can a government last that fears 15 year old girls?”

“In 1970 when I was 15 years old, I began attending the Maraş teachers’ school,” she says, and continues:

“School years were the ones when we began to read books. We read everything we could lay our hands on. We had begun to learn a few little things about contemporary thought. We were eighteen in the group. We exchanged books among ourselves and then, exchanged on what we had learned. I would have liked to say that none of us had thought that these exchanges would exclude us definitely from schooling. But, unfortunately, those where the infamous days when the grey wolves roamed. A few months after our removal from school, Deniz Gezmiş et friends were sent to the scaffold. To tell the truth, today we understand while looking back that those “obvious days” have never changed in Turkey. Each time, they have simply taken on a different disguise between the civilians and the military.

Our exclusion was seen as a scandal and provoked reactions. I will never forget journalist Uğur Mumcu questioning the government in the columns of one of his chronicles: “How long can a government last that fears 15 year old girls?”

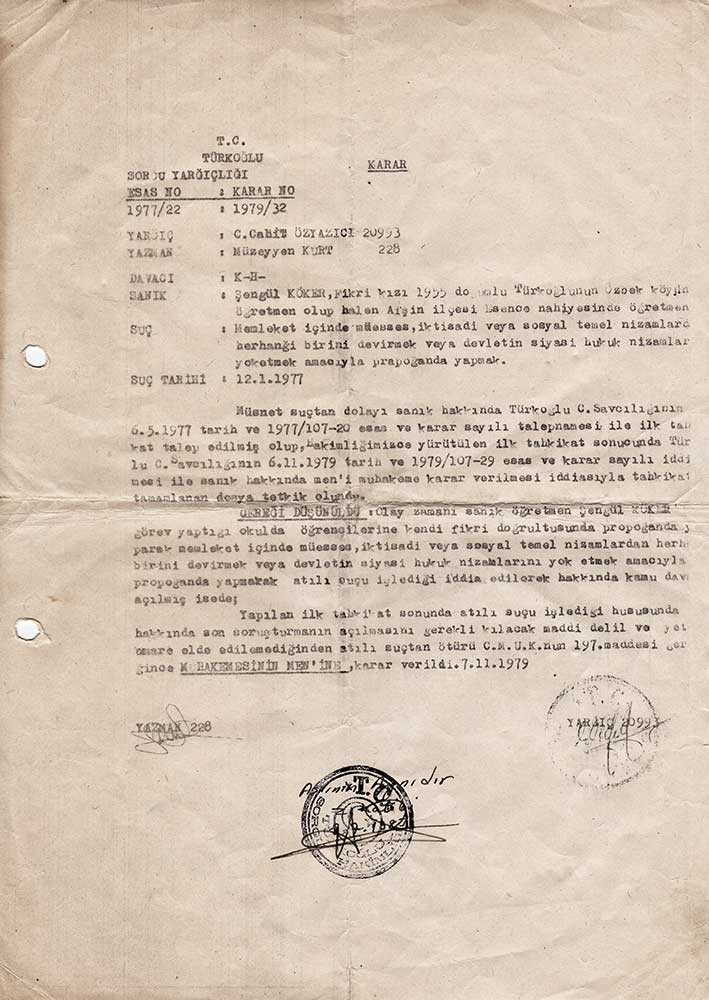

The judicial process and the annulment of the decision excluding us from school cost us two years of our lives. The verdict deigned to allow us to attend an educational establishment outside our environment, meaning, in another town! That is how my exile began. I was able to finish the four year teacher’s training program in six years. This was not my first exile in order to study. I attended six schools in Kayseri Antep, Adiyaman Besni, Adana and finally in Mersin where I received my teacher’s diploma.

My exclusion from the school in Adana was also interesting.

After the school in Adiyaman, I went to Adana. Not a single school wanted to accept me in that town. At the time, the government consisted of the Erbakan-Ecevit coalition and Mustafa Üstündağ was the the Minister of National Education. My father no longer wanted me to study. So my mother went to meet with the minister in person. Following the arrival of a bulletin from the ministry, my registration was accepted at the school in Adana. My stay in Adana lasted as long as the coalition did. When it ended, knowing that my presence “slightly bothered” the director in such a way that I couldn’t stay, I transferred to a school in Mersin where I finished the program.

“Is Fikri Köker’s communist daughter here?”

My life as a teacher has nothing to envy to my school days. Or I should say, they did not lead me to regret them, that would be a more precise way to put it. As soon as I finished my schooling I was directed to Türkoğlu, Maraş district. My family also lived in Türkoğlu. Maraş is a small town, Türkoğlu is even smaller. The week before classes started, an inspector from the National Education was to hold a meeting for the region’s teachers. All the teachers. We went. The inspector came in, we stood up. He opened the meeting with a question that surprised everyone.

- “Is Fikri Köker’s communist daughter here?”

The new teachers looked around for Fikri Köker’s communist daughter and those who knew me looked at me discretely. I was still very young, I was attached to my ideals. In fact, my pride impelled me to stand up and introduce myself.

I stood up and smiled “Fikri Köker’s communist daughter is here, Sir”, I said, “is the fascist inspector honoring this meeting with his presence?” That same day, they prepared the paperwork and I was sent to a village in Maraş. At the time, they spoke of a ‘posting’, they spoke of a ‘decision’, they said ‘we’ve been ordered’, but every time, we knew what it was: EXILE…

“Speaking another language than Turkish is prohibited in school!”

Frankly, with the inspector looking for Fikri Köker’s communist daughter, I understood how the rest would proceed. During my life as a teacher I was exiled eight times, suspended for a year, although “suspended” is a bit of a mild way to put it. I was a clandestine…

During my years as a teacher, the number of people who thought like us, who joined us, with whom we shared our fate, kept growing. The more we grew, the greater became the violence of fascism.

I always taught in Kurdish and Alevi villages. And I did not only teach there. Everywhere I went, I lived among the villagers. We held meetings with the inhabitants, we met with the young people every night, we discussed with them. I prepared seminars for them. All I told them about was nothing other than their own lives, really. They were from Kurdistan and I told them how to be from Kurdistan. Under the conditions of the time, talking about all that was prohibited and looked upon poorly. I’m talking about forty years ago, but I’m thinking of nowadays at the same time. Concerning the Kurdish question, State intelligence has not evolved at all, and goes on resisting the evidence. How sad!

Within school boundaries, speaking another language than Turkish was forbidden. Of course, the objective being to prohibit speaking in Kurdish. As if not expressing the prohibitions as such made them invisible. My pupils were taking their first steps into a school without knowing a word of Turkish. Those were the children learning Turkish, only in school. The language is different, the lands are the same. All the children, Kurdish, Alevi. I considered this prohibition cruel. Of course, I did not prohibit. Because prohibiting Kurdish was imprisoning them in deep silence.

One day during school hours, the door opened and an inspector walked in. None other than the inspector who had been looking for Fikri Köker’s communist daughter…in person. He told the children to place their school bags on their desks and started searching through them one by one. I said “Mister Inspector, you are not from the police, attend to your own work.” At that moment the children started talking to one another, in Kurdish. After the inspector left, the gendarmes were not slow in showing up. They shoved into my hand the document stating the end of my link with the school, and left. Even if I had accepted this decision, the villagers didn’t accept it. They wanted us to go the prefecture together. We went. The villagers simply wanted to stop them from relieving me from my duties in that school…But “teacher Şengül incited the Kurdish people to rise up against the State”. Teaching is one thing but because of the trial that was opened against me, I spent one year in clandestinity. And it was thanks to clandestinity that I was able to avoid being tortured, and imprisoned as were my friends.

I went back to work in Konya, Sarayönü. My two children were born as exiles. My departure from Konya was no different from that from other towns. We arrived in 1981 and there was no place for us to live. I picked up my two suitcases and my two children and, under the escort of gendarmes, I left Konya. And, ten days later, the country. I knew that teachers who were forced to leave their job this way were usually taken a few days later and tortured. Most of my friends, following heavy sessions of torture, spent years in prison. When I left the country, I had to leave my children with someone because, believe me, I had no idea what to expect of the road of migration.

“My children were my hope, but my daughter was the hardest and greatest struggle in my life”

It was a difficult journey. We left Istanbul by bus, crossed several countries and arrived near the Jura, in Switzerland, which was our terminal. For the first few days, I stayed with people who were close to the family. I looked for work. That was the only way to bring over my children. Because I didn’t know yet what asylum meant. I learned in an establishment where I had been seeking for work. “You are entitled to asylum, you cannot work in a country in which you are a clandestine”. So I asked for asylum.

Afterwards, I found a job in a watch factory. When I donned the blue work outfit, it felt odd, but after a while, I began to understand what it was like, looking out on life from the perspective given by this garb. I was at once a refugee, a worker and a woman. I was at a triple disadvantage, exploited three times over…

I could then see social differences much more clearly. I signed up with the Communist Party of the Jura. During that period, my previous life appeared even more precious to me. The forbidden books back in my school days, those we read in secret, they were right, and we who lived through exiles were right also, but we hadn’t won yet.

I don’t think there is a single woman who doesn’t experience the difference in an active life, even today. For example, the manifesto from the strike women carried out last June also contains an article about the discrimination experienced by women refugees. Equal salary, equal treatment…

My desire to fight was still red-hot but I had children and I had to work. My daughter was the first to come under a fake passport. My son stayed in Turkey. I had been at the point of separating from my companion and that meant I was at risk of never seeing my son again. My companion might have chosen not to send him over, because of the divorce. I had even taken the risk of rescinding my asylum request. There is a name you may know, that of the poet Edibe Beyazıt, alias Ediba Sulari. She was the daughter of the poet Sulari. We lost her during the Madımak massacre. I went to Istanbul with Edibe Beyazıt,‘s passport. I went looking for my son and I brought him over here.

As my children grew, the problems grew along with them too. It really was not easy working as a single mother with two children. You go to work but your head is thinking about your children. I lived that way for many long years. I worked and raised my children. But I have to say that the hardest struggle of all was my attempt to save my daughter. On her 16th birthday, I learned my daughter was taking drugs. A familiar behavior for a teenager. She fell in love. Her boyfriend was also an addict. For a whole year, I tried to wrest my daughter from that relationship, with no success. And shortly after, I learned she was pregnant. My daughter Funda was placed under State protection.

My daughter was an addict and about to become a child-mother. I couldn’t accept that. I was very worried. I had to make extreme efforts so as not to make a wrong move. I spoke with the director of the hospital. I tried to explain that my daughter was much too young, that she couldn’t possibly take care of a baby when she couldn’t even take care of herself. Since she was under State protection, Funda needed confirmations from the canton, doctor, the gynecologist and the social assistant in order to obtain an abortion. All of them were aware of the situation but all they kept telling me was that everything was under control. “Because this is Switzerland, not Africa!” That was the social assistant’s response at the end of our meeting.

I requested that my daughter be taken into a detoxication center after the childbirth. My request was also rejected. I don’t think the social assistant was against this idea, but I know the directors refused for budgetary reasons. One of their worries was also that addicts like Funda avoid them, out of fear of the clinics, in other terms, the fact a dependent would be leaving the State protection program!

After a few years Funda reached a point where she could no longer care for her child. My grandson was also placed under State protection. I questioned the canton government through the media, over and over again. I howled “save my daughter” but I don’t think my voice was heard. My daughter developed gangrene and lost her arm. On the day she came out of surgery, I started procedures against the doctor, the social assistant and the director of social services. The doctor’s declaration in the file stated they had never object to treatment for Funda. No one asked “you did not object, but did you have her treated?” I lost my daughter in 2010. My grandson lost his father when he was 6, he lost his mother when he was 13. The trial ended four years after my daughter’s death. We didn’t win, we didn’t lose. The law is the same everywhere.

Today, I am 65 years old and when I look back, the only thing I can say is that it’s been very hard. I was the first to arrive in the canton from Turkey. After me, many people have arrived from Turkey and from Kurdistan. Many people I can described as being from my lands, my own… In the hardest periods, my friends in the Party have been by my side. They are all natives of the canton.

I have always been endangered by the machist State, the patriarchal society. I was discriminated against by my own, most of all, because I was divorced. I worked, I thought differently. In our tiny society, there exists a notion of “decency” devoid of meaning. Doesn’t the very existence of the notion of decency empty out our souls? That is yet another reality! A concept of decency which, instead of resting on the fact you are someone upright, honest, earning your bread at the sweat of your brow, gets shoved under a woman’s skirt and her marital status. We should have shattered that chain of archaic thoughts a long time ago, but there are some people who prefer to keep them alive still. And they want to grab by the collar those who wish to stay outside, in order to drag them inside. The fact they were unable to drag me in was the reason for their cruel attacks. But enough said on that…

These past few years, a number of asylum seekers have arrived because of the political problems in Turkey and in Kurdistan. All of them are true political refugees. When I look at them, I am pleased for myself, but worried for my country. Because everyone living close to me for years has seen that Şengül is not alone, there are many people who think like Şengül, who live like Şengül. I am more optimistic than I was in the past.

Our freedom and our hope are what provide our links to life. My life was spent on the roads of exile. As I said, it was not easy. But despite all the pain, if I can look up at the sky, at all the shades of blue and experience them, that reinforces my conviction. In closing what I would like to say to women refugees is: stay upright and stand on your own two feet, fight. Your fight is the only thing that will keep you standing in the country where you are attempting to rebuild your life. There is no other way.” That is how big sister Şengül ends her story.

In listening to Şengül I understand that if you are exiled, you will never have a terminal, that your goods will always fit inside two suitcases, and that the roads become your home. What is more, this feeling that you do not belong to the country to which you immigrated will never leave you. Big sister Şengül, having certainly lost the feeling of belonging to her country, willfully abandoned the Turkish nationality in 1994…